You might think that a guy who has performed or consulted on 17 gold or platinum recordings by artists like Mel Tormé and Stevie Wonder — and on hit films like Good Will Hunting and Pulp Fiction — would be famous for playing his instrument. In the case of Daniel Levitin, you’d be wrong.

It’s Levitin’s work as a researcher in neuroscience and cognitive psychology that has brought him international attention, including over 2,200 articles in the press (17 of them in The New York Times), multiple interviews for National Public Radio and TV news shows, and wide popularity as a public speaker.

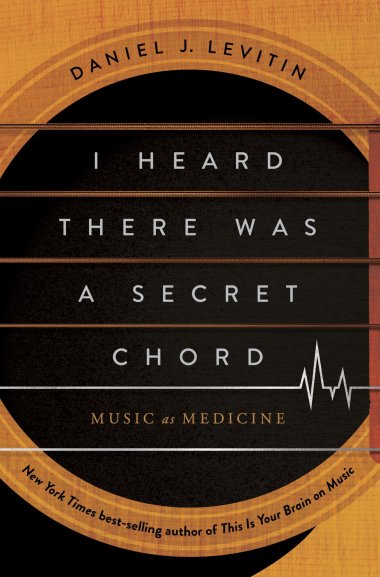

His roughly 300 journal articles cover a range of topics, but he is most acclaimed for his research on music and its effects on brain function. Working at Stanford University and then McGill University, Levitin has shared his discoveries and ideas in such bestselling books as This Is Your Brain on Music (2006), The World in Six Songs (2008), and most recently, I Heard There Was a Secret Chord: Music as Medicine (2024).

On July 6, Levitin is scheduled to speak at a symposium at Festival Napa Valley. Before then, he talked with SF Classical Voice about his latest book and his research in music cognition.

In an NPR interview, you were asked how music is like medicine, and you said something to the effect of: “If you believe that chewing on willow tree bark will alleviate pain, then it is medicine.”

I think the point I was trying to make is that we were given all these folk remedies from [ancestors]. And some of them pan out, some of them don’t. The job of a scientist is to figure out which of them are true and which of them are coincidence. You know, the willow bark turned out to be right, and so did the seed of a poppy.

For all the doubters still out there, can you explain in what way music is akin to medicine?

There’s a bunch of studies that are supporting this, but I think there’s a cultural bias that we consider that medicine is either a product that you get from a pharmacist or it’s a treatment you get from a doctor.

But medical schools will tell you that that’s too limiting a view. I mean, if you’ve got asthma or a lung obstruction or low SpO2 [oxygen saturation] levels, you take oxygen out of a tank. Oxygen is all around us, but it’s medicine in that case — as is the willow bark or valerian root, which is akin to Valium, or vitamin D, which we get from the sun.

To be more precise, though, we now have ample evidence that music can help treat a variety of injuries and diseases, including both mental and physical disorders. And I think the very best case is Parkinson’s disease.

Do we have a pathway for how music helps that?

We do, and part of the effort of scientists is to understand not just that it works but how and why it works. In the case of Parkinson’s, many patients lose the ability to walk. The circuit in the brain that guides them to put one foot in front of the other at a particular time and in a particular sequence [stops functioning].

You can’t put your right foot down twice in a row. I mean, it seems obvious, but if you were programming a robot to walk, you’d have to give very explicit instructions. [In someone with Parkinson’s] those circuits become degraded. But if you play music at the tempo of the person’s natural walking speed, after about two and a half seconds, neurons throughout the brain synchronize to the tempo of the music and act as an external guide that allows them to walk again.

Can it be said that a music-appreciation gene, because it obviously has an adaptive function, spread through human populations as a result of natural selection?

Well, I argue that in Six Songs, and Steven Mithen argues it in The Singing Neanderthals. I think it’s obvious that that there’s cultural transmission of music, but there’s [also] a genetic predilection for it.

Chimpanzees don’t have the same predilection for music.

Right, and I’ve done some work with my McGill colleague Michael Petrides on that. The reason [chimps] don’t have it is they’re missing a particular brain structure in the prefrontal cortex that we evolved, that no other primate has evolved, and it’s one that ties together the parts of the brain that attend to pitch and rhythm and structure in sound. So chimpanzees have a hoot, which is pitched and rhythmic and has a structure, but it’s not an elaborate structure.

To have music, you need to be able to appreciate long form — at least a three-minute pop song or 30 seconds of “Happy Birthday.” And there’s no evidence that any animal can do that, even birds, who have very complex structural imprinting for music. Birdsong isn’t song to the birds — it’s their way of communicating, the way we use speech. There are several converging pieces of evidence for that. One is that humans will sing alone, by themselves. Birds will not. Humans will vary a melody or a rhythm; they’ll do things in different tempos. Humans [compose] their own music, and birds don’t.

Is it possible that humans used music to communicate before they were using elaborate verbal structures?

That’s unknown until Peabody and Sherman resurrect the Wayback Machine. But Mithen’s book is excellent [on this topic]. And my own work at Stanford with Vinod Menon has shown that the structures in the human brain that respond to music, those are all biologically — that is, phylogenetically — older than the speech centers. So it suggests strongly that music preceded language.

What we speculate is that early communication sounded a lot like the teacher in the Peanuts cartoons. You know, “Wah, wah, wah, waaah.”

In The World in Six Songs, you write about the role of music in human socialization and its importance in promoting social bonding.

Music in general, under the right circumstances, causes people to feel closer to one another. My friend [bassist and songwriter] Victor Wooten has this wonderful way of putting it, which is that if you go to a political rally or a sporting event, your hope is that the other half of the population will lose. But if you go to a concert, you want the performers to win. You want the other audience members to win. You don’t care who they voted for or how much money they have or what color their skin is.

There are people who believe they’re not musical because they haven’t studied or they don’t have a beautiful voice or they can’t match pitch reliably. What would you say to such people?

I think it goes against our evolutionary history to think that way. Until about 500 years ago — and still — over most of the planet in preindustrial societies, everybody sings.

My friend Jim Ferguson, who was the chair of the anthropology department at Stanford, went to do field work in Lesotho, the small country embedded in South Africa. After he had won the trust of the tribespeople there, they invited him to a ceremony, and they asked him to sing. He said, “I don’t sing,” and that made no sense to them. They said, “You can talk. Of course you can sing.”

But 500 years ago, when the first European concert halls were built, we created this artificial division between expert performers and the rest of us. Now, most people are self-conscious about singing in a way that they aren’t about other things. If you go to any city playground, there are going to be a bunch of people playing basketball with no aspirations to be Steph Curry. And I’ve never heard anybody say, “I’m no Martin Luther King, so there’s no point in me even talking.”

What tasks do musicians perform regularly that stimulate neural connectivity?

Well, deep listening — meaning not just having [music] on as sonic wallpaper but really listening, whether you’re consciously attending or letting it send you on a flight of daydreaming — helps to promote neural growth, neuroplasticity of new circuits. And certainly, performing requires some kind of muscle control and a feedback loop where you intend to execute some action.

All sound begins with movement — either air through the vocal cords or through the tube of a trumpet or clarinet or plucking or strumming or banging on something. That movement is something that you intend to do, and then you listen to the result. If it’s not what you intended, you practice harder, or you adjust, as we do in jazz, and do something different. That feedback loop is engaging because it’s immediate. There are few things we do, other than speaking, where we get such immediate feedback that we can correct. That is very stimulating to the brain.

I would say playing an instrument is probably among the most complex activities that humans do. I’ve just been learning, in the last five years, to not play the notes but play the music. And then the phase after that is to not play the music but play a story. I’ve been tutored in this by Mari Kodama, the wife of [conductor] Kent Nagano. At her level, a concert pianist who performs with the best orchestras in the world, it is no longer about turning the notes into music. It’s about turning the music into a very personal story that has a trajectory.

What are you going to cover in your talk at Festival Napa Valley?

I have a PowerPoint presentation, and I’ll show the example of Parkinson’s. I’ll talk about Gabrielle Gifford’s recovery from a [gunshot] wound that rendered her speechless and how she learned to speak again to music. I’ll talk about pain and mental disorders, like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as the finding that music can boost your immune system.