How does a professional singer build a career?

If you’ve had a big breakthrough and you’re performing at an international level — among American singers, think mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton or tenor Michael Fabiano — opera houses come to you. Fabiano’s 2024 schedule was typical of such artists. He sang in Spain, Great Britain, the United States, Germany, Austria, and Italy.

But if you’re primarily active in a particular U.S. region, your career has a different shape and makes different demands. To find out more about this latter group, SF Classical Voice recently spoke with mezzo-soprano Leandra Ramm, tenor Alex Boyer, and bass-baritone Chung-Wai Soong about their professional paths.

Getting Started

Unlike string and piano players, who often start on their instruments before age 5, singers need some physical maturity before voice lessons make sense.

Ramm grew up in New York City. Her mother was a pianist and dancer, and their household was filled with classical music. One formative experience was hearing another girl sing a Whitney Houston solo in a talent show in second grade. Ramm said she remembers thinking, “That’s what I want to do.” She joined the Young People’s Chorus of New York City and started working with a voice teacher at 14. By the ninth grade, she was sure she wanted to be an opera singer.

Boyer, who also grew up in the NYC area, started on cello in the third grade and played into his teens. “I never practiced,” he confessed, “though I loved playing in the orchestra.” At his high school, choral singing was required, and he performed in musicals and plays. During his junior and senior years, he studied classical voice.

Ramm and Boyer both attended Manhattan School of Music, though Boyer would get his undergraduate degree first from Boston University. After graduation, Ramm participated in young artist and apprentice programs at Arizona Opera, Toledo Opera, and other companies. Boyer is a Merola Opera Program alumnus and was a Santa Fe Opera apprentice singer.

Soong started even later. Born and raised in Malaysia, he was at university in Melbourne, Australia — studying accounting, economics, and econometrics (“Fields I have practically zero interest in,” he told SFCV) — when he began singing lessons “on a lark.” Before he knew it, he was entering local competitions. He joined the young artist program at the Victoria State Opera in Melbourne and subsequently moved to San Francisco in 1992 to continue his vocal studies.

Steps to the Big Stage

Unusually, Boyer spent five years as a resident artist at Opera San Jose. (Two or three is more common.) OSJ is unique among U.S. opera companies in that it’s closer to the model of a German “Fest” company. Singers receive salaries and health insurance and are expected to perform in most or all of the productions in a given season.

Owing to the foresight of its founder, the late mezzo-soprano Irene Dalis — who purchased apartment buildings that the company still owns — OSJ is also able to provide housing for its resident artists, giving them an unusual degree of financial stability early in their careers.

“I sang something like 22 or 23 leading roles while I was there,” Boyer told SFCV. He noted that in other residency-style programs, it’s more common to sing only small roles and cover (or understudy) leading ones. But there are limits, he explained. “Irene Dalis was generous enough to excuse me from several roles that wouldn’t have been appropriate for my voice type, like Count Almaviva in The Barber of Seville.” Boyer is a heroic tenor, and Almaviva is a lyric coloratura role.

Boyer’s career has been almost entirely in opera, with a sprinkling of tenor solos with orchestra (for example, in Verdi’s Requiem). In addition to his many roles with OSJ, he has performed with the Bay Area’s Island City Opera, Livermore Valley Opera, Festival Opera, West Edge Opera, Pocket Opera, and San Francisco Opera. Beyond, he has sung with Los Angeles’ Numi Opera and Hawaii Opera Theatre.

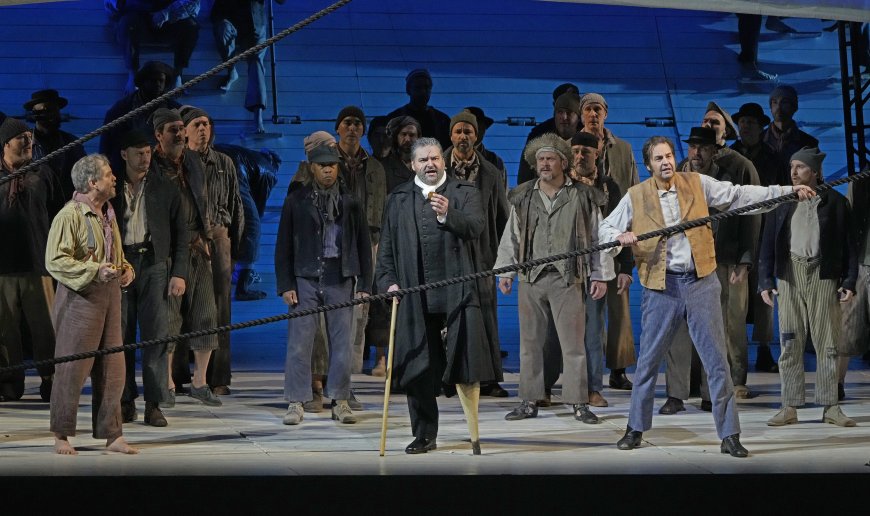

He has also covered several roles at Dallas Opera and New York’s Metropolitan Opera and recently made his Met debut in dramatic circumstances: singing the starring role of Captain Ahab in Jake Heggie’s Moby-Dick for three performances in March when tenor Brandon Jovanovich had to withdraw due to illness.

“There was no time to be nervous,” Boyer said. “You get the call sometimes with a good amount of time before you have to go on and sometimes not. In this case, I was called in the morning, so I got there a couple of hours before curtain. After I met with Lenny Foglia, the director, I went out onto the stage and just barked a note out because at that point I had never sung on the stage.”

Boyer had already covered Ahab elsewhere and sung the role at Chicago Opera Theater, so he was no stranger to it. At the Met, however, covers get to rehearse together but don’t necessarily get any advance onstage time. Boyer was grateful for the support he received from rehearsal and music staff and everyone else involved in the production.

He’s spent most of the last six months in New York, covering various roles for the Met, and he won’t be back in the Bay Area (where he lives) for a few more weeks. This summer at West Edge Opera, he’s scheduled to sing Senator Robert F. Kennedy in the world premiere of Dolores, composer Nicolás Lell Benavides’s opera about civil rights and labor leader Dolores Huerta.

Chorus as a Career

Ramm’s and Soong’s careers have taken them in a multitude of directions, all at the same time. Both have sung with the Bay Area’s many regional opera companies and with small companies elsewhere, but professional choral work is the core of their careers.

Soong has been a paid member of the San Francisco Symphony Chorus for 32 seasons, starting in Herbert Blomstedt’s last year as music director of the orchestra. Ramm, who moved to the Bay Area 11 years ago, is also a paid member of the SF Symphony Chorus. These union positions currently provide a minimum salary of $22,053. Both are also union members of the extra chorus at SF Opera, called upon when more than the regular choristers are needed for a particular production (for example, 2023’s Lohengrin and next season’s Parsifal).

Ramm and Soong were also members of former SF Symphony Chorus Director Ragnar Bohlin’s Cappella SF, and both currently sing with the Philharmonia Chorale. Beyond those positions, the mezzo-soprano and bass-baritone each perform with a dizzying array of local organizations, in solo and ensemble capacities. That’s what it takes to have a full-time singing career in the Bay Area.

Ramm sings with the chamber choruses Voices of Silicon Valley, Aeternum, and Vox Humana SF. She also teaches voice at several places and has recorded CDs and written a book. Her most recent album, Watching Glass, I Hear You, includes new works written for her and is available on major streaming and purchase platforms.

Soong is a staff singer at Grace Cathedral and a member of the American Bach Choir. His work has taken him to Hawaii Opera Theatre and to the New York Philharmonic Chorus for the opening of the remodeled David Geffen Hall in 2022. (He revealed that he has had up to 14 W-2 and 1099 forms to deal with at tax time.)

Coordinating all of this professional activity requires considerable attention. “I manage my calendar like a fiend,” Soong said. “It is color-coded, and I go through it with a fine-tooth comb all the time.” On one recent day, he had two rehearsals and a performance to attend.

Ramm has four children, ranging in age from 10 to just under 1 year. Her husband Jim Coniglio and two older children are also involved in the performing arts. “It’s very challenging,” she said. “We have weekly meetings, ‘planning meetings’ we call them, where we look at the upcoming week and figure out who has to be where at what time and what babysitters we need and can grandma help this day?”

Sometimes there’s overlap. Ramm’s 10-year-old, James, was the young Duke Godfrey in SF Opera’s recent Lohengrin and has been a supernumerary in other company productions, while her 8-year-old, Siena, was one of the children in 2024’s The Handmaid’s Tale and a supernumerary in 2023’s Il trovatore.

Making Ends Meet

Boyer, Ramm, and Soong are all able to make their livings as professional singers. “I’ve been very fortunate,” said Boyer, whose only other job has been summer paralegal work during his school years.

When she was younger, Ramm worked in both musical theater and as a singer on cruise ships. For his part, Soong has held administrative positions with different businesses, including Pocket Opera, and ran his own event and catering company at one time.

Boyer and Soong declined to discuss income specifics, but Ramm disclosed that her income from singing and teaching is typically in the range of $75,000 to $90,000 a year.

The challenges of a performing career have an impact on all singers and their families, children or no. Boyer met his partner of 15 years, Tori Grayum, when he was a resident artist and she was an associate artist at OSJ. Grayum no longer sings, but she understands how the business works and that it comes with separations. Soong met his partner, philosopher Noam Cook, in the SF Symphony Chorus. “We’re lucky that we get to spend that time together,” Soong said.