When the Metropolitan Opera commissioned John Corigliano to write his first opera in celebration of the company’s centennial in 1983, he pulled out all the stops. The result, premiered in 1991, was The Ghosts of Versailles, a maximalist spectacle layering Mozartian pastiche, lush romanticism, and 20th-century dissonance into storylines that swirl through time, the afterlife, and operatic history — by turns haunting, comedic, and moving.

Ghosts was an inspired choice in 2025 to commemorate another milestone: the 50th anniversary of the Shepherd School of Music at Houston’s Rice University. The school’s recent production, which opened April 11 to a sold-out house, met Corigliano’s vision with equal ambition in a compelling performance that made clear Shepherd’s educational philosophy and aspirations for the next 50 years.

Tapping soprano and educator Patricia Racette to direct underscored that intention. Racette previously starred in the opera’s leading role — the ghost of Marie Antoinette — in Los Angeles Opera’s acclaimed 2015 production, the recording of which went on to win a Grammy Award. She now brings that same musicianship to her work with emerging singers.

“She trusts the [students’] instincts and treats them like professionals,” said Joshua Winograde, director of opera studies at Shepherd and formerly senior director of artistic programs at LA Opera. The score of Ghosts itself gave all 32 vocalists in Shepherd’s opera program named roles onstage.

Ghosts was all the more fitting performed in a venue that remarkably echoed the opera’s setting: the Brockman Hall for Opera, which opened in 2022. “That building’s completion is one of the major achievements of the 50 years of the Shepherd School,” said Dean of Music Matthew Loden. Designed by U.S. firm Allan Greenberg Architect, the hall features a 600-seat theater with state-of-the-art capabilities that was acoustically modeled on the Royal Opera of Versailles. Staging Ghosts — set in that very palace — brought the connection full circle. “It’s our own little Versailles here in Houston,” said Loden.

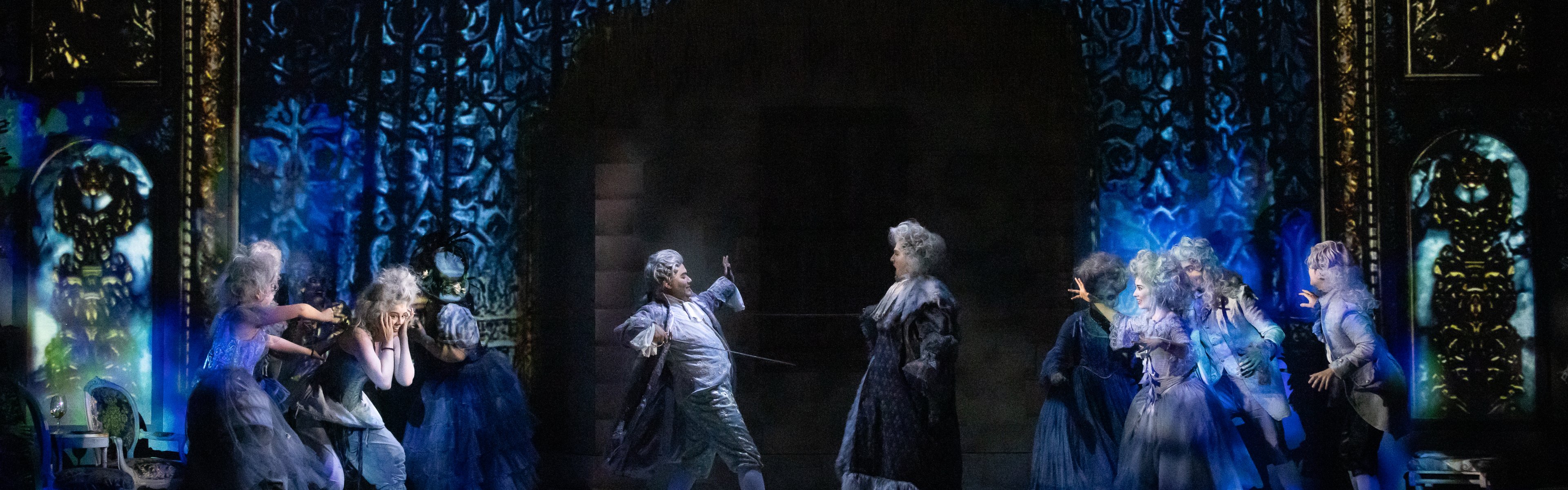

The production’s professional-level craftsmanship was clear from the arresting opening scene, introducing the ghostly afterlife of Louis XVI’s court. Amid projected gilt rococo patterns blurred by haze, dead courtiers in tattered tulle and harried wigs moped about in eternal ennui; the cast leaned gleefully into their comic absurdity throughout the evening.

Here, from her first appearance as Marie Antoinette, soprano Anna Thompson anchored the opera’s emotional center. Perpetually reliving her gruesome execution and the fiery chaos of the French Revolution, the verklempt monarch pines to live again. Thompson brought power and grace to “They are always with me,” a sorrowful aria with jarring shifts between song and speech over roving harmonies.

Marie Antoinette’s deceased partner in dramatic sincerity is the playwright Beaumarchais, the real-life author of the Figaro trilogy, this part sung with warmth by baritone Gabriel Natal-Báez. To relieve the court’s boredom — and driven by his unrequited love for the queen — Beaumarchais writes a new opera, enlisting his prior characters Figaro, Susanna, and the Count and Countess Almaviva to carry out a supernatural plan: sell Marie Antoinette’s infamous diamond necklace and rewrite her fate.

The opera then spirals into a nearly indecipherable play-within-a-play, winking toward the convoluted storyline of The Marriage of Figaro; the wine-drunk Louis XVI, portrayed by bass-baritone William Dopp, quips that he could never follow it.

This dramatic confusion unfolds in a broader narrative structure designed to serve the music at every turn. Corigliano, who attended the Shepherd performances, explained in a preconcert talk how he and librettist William Hoffman together developed “a world of smoke and mirrors” that could shift into the 18th century and then into fantasy. The story was “invented to fix a musical need,” to move beyond neoclassical conventions and allow for the cluster sounds and orchestral ideas of the late 20th century.

Baritone Collin Jumes leaned into the comic roots of his role as Figaro, especially during the slapstick shenanigans of the Turkish embassy scene. As the villain Bégearss (drawn from Beaumarchais’ third Figaro play, The Guilty Mother), tenor Kellan Dunlap embraced the character’s venom, whipping the mob into a murderous frenzy in the aria “Monarchy. Revolution. It’s all the same to me — Women of Paris, listen!”

Some of the most poignant moments emerged in ensembles, such as the charming Mozartian quartet “Come now, my darling,” and the serene Act 2 quintet “O God of love, O Lord of light” featuring the imprisoned Almavivas, Susanna, and Marie Antoinette. The connection between characters — and with the audience — was palpable.

Under conductor Benjamin Manis, the Shepherd School Chamber Orchestra navigated the score’s shifting styles with agility. The orchestra was most compelling in the Act 2 interlude — a musical metabolism of Marie Antoinette’s realization of Beaumarchais’ sacrifice. Solo woodwinds traded a fragile high-register motif, while declamatory brass brought clarity and resolve as she ultimately chose not to alter history. In such a dense score, some balance issues inevitably arose, particularly affecting the male singers.

As described by Winograde, opera studies at Shepherd function as a kind of laboratory: a space where students test, integrate, and apply what they’ve learned, reflecting Rice’s broader research ethos. This production of Ghosts stood as a testament to the results — and potential — of that approach to training the next generation of artists.