This concert season, the classical world has been commemorating the 150th anniversary of the birth of musical revolutionary Arnold Schoenberg. To mark the occasion, the Herb Alpert School of Music at the University of California, Los Angeles, where Schoenberg taught from 1936 to 1944, has been holding numerous special events over the last few weeks, including lectures, seminars, and panel discussions dealing with the composer’s legacy and influence.

One of the questions under discussion is Schoenberg’s aesthetic convictions, expressed in his famously uncompromising motto “If it is art, it is not for all. If it is for all, it is not art.” The conflict is right there in the title of Schoenberg in Hollywood, Tod Machover’s multimedia high-tech opera (really a music-theater piece), which received its West Coast premiere at the Nimoy Theater on Sunday, May 18, as the centerpiece of UCLA’s festival for the composer. There are two more performances, May 20 and 22.

Associated most prominently with his hometown of Vienna, where he was one of the so-called Second Viennese School and helped create 12-tone music, Schoenberg (1874–1951) lived his final 17 years in Los Angeles, having escaped the Nazi regime and its virulent anti-Semitic policies. During this last and arguably happiest period of his life, Schoenberg had the economic and personal freedom to pursue his art and left a lasting imprint on L.A.’s musical and cultural community. On the evergreen grounds of UCLA, below palm-lined Sunset Boulevard, the music school’s main building and library both bear his name.

Schoenberg in Hollywood, originally staged by Boston Lyric Opera in 2018, has received a loving revival at The Nimoy, supported by the Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience at UCLA and directed by Karole Armitage, a veteran of the New York dance world and Broadway. Here is a noble and commendable effort, but the mundane musical substance, choppy dramatic structure, and at times gimmicky production values fail to bring alive what Machover calls “one of the great stories of our time,” the tale of Schoenberg’s personal and creative liberation after decades of struggle against critical and religious persecution in Europe.

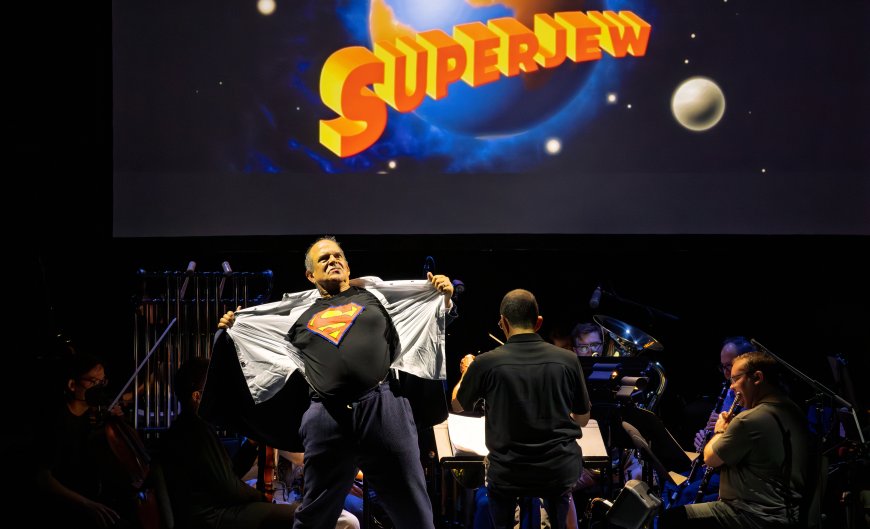

The libretto flies off in so many confusing directions that we leave the show unsure of what the message is supposed to be. Is it that Schoenberg wanted most of all to be leader of the Jewish community (“Superjew,” complete with appropriated Superman outfit)? Or did he want to be first among all composers past and present? Or was he always in search of a firm identity — Austrian, German, Jewish, Protestant, American? Maybe he just really wanted to make it as a Hollywood composer?

Constantly running visual effects (documentary clips, newly created footage, animation, and still photos) define the staging. Acoustic and electronic music by Machover, fragments from Schoenberg’s own works, quotes from Hollywood film scores, and American folk tunes crowd the stitched-together score.

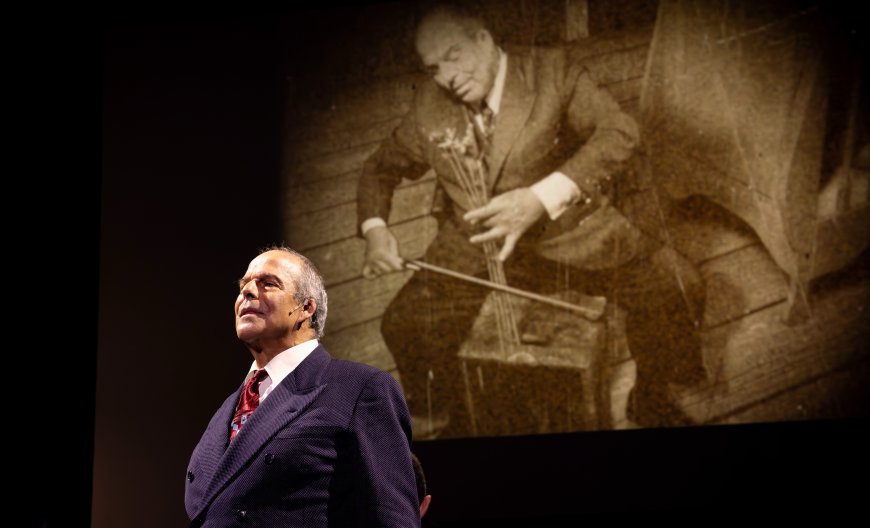

In the title role, the hardworking baritone Omar Ebrahim feels at times almost incidental. The angular recitative-style music that Machover gives the Schoenberg character (and two other cast members who take on various parts) rarely conveys the emotional pathos of the drama, instead employing the voice as another instrument in the ensemble. (This may be a reference to Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme style in works like Pierrot lunaire.) An ensemble of 15 players, ably conducted by Neal Stulberg, serve as background without advancing or commenting on the action.

Machover and librettist Simon Robson begin their story (based on a scenario by Braham Murray) with Schoenberg meeting Hollywood wunderkind film producer Irving Thalberg, who tries to persuade the composer to write a score for The Good Earth. Predictably, Schoenberg rejects the idea of changing his music to suit the demands of a director. For Machover, the Hollywood connection becomes the key to the narrative, a way to explore “the tricky relationship between uncompromising art and mass appeal, and of whether — and how — art can change the world.”

Schoenberg’s roller-coaster biography unfolds in various Hollywood film styles (film noir for his troubled early love life, Westerns for his arrival in the U.S.) and familiar movie and TV tunes (“As Time Goes By” from Casablanca, Roy Rogers’s “Happy Trails”). These pastiches create a comic effect but distance us from Schoenberg’s feelings and emotional states.

Soprano Anna Davidson inhabits numerous identities (Schoenberg’s wives, a young girl) and displays impressive vocal talent, although she is rarely given the opportunity to show it. Tenor Jon Lee Keenan assumes various roles (Thalberg, a Nazi sympathizer) and is the show’s most accomplished actor. He and Davidson frequently intone the refrain of reinvention on American soil: “Neue Welt! New World!”

Schoenberg in Hollywood reaches a cacophonous climax in “Schoenberg’s Vision,” a mash-up of all the styles that assaulted and attracted the composer in his career, accompanied by a rapid-fire collage of on-screen images. Schoenberg then awkwardly disrobes onstage, revealing his “Superjew” costume. Then he sings, in something of a non sequitur, about his desire for unity and barks the familiar film command — “Action!”

In his composer’s note, Machover writes that “the whole opera could have been filled with tennis matches with George Gershwin and garden parties with Charlie Chaplin,” but he decided against that approach. It would certainly have been more fun.