Tatsuya Shimono, one of Symphony San Jose’s favorite guest conductors, returned to the California Theatre on Saturday, May 10, to lead a coruscating, sandblasted performance of Gustav Holst’s The Planets.

The enhanced orchestra — it takes a lot of extra players for a medium-sized ensemble to stage a work this large — tore into the music under Shimono’s snappy, commanding direction. The climaxes, the whoosh at the peak of “Uranus, the Magician” and even more so the conclusion of the hymn theme in “Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity,” had all the flash, vigor, shine, and color that make for an exciting and spectacular orchestral performance.

And remarkably, Shimono conducted the entire suite at this level of intensity. “Venus, the Bringer of Peace” was as rigidly rhythmic as “Mars, the Bringer of War,” just less vehement in presentation. The opening of “Neptune, the Mystic,” traditionally a soft and rather distant movement, was surprisingly insistent and threatening. The only extended passage of serenity in the entire performance was the ending of “Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age.”

The orchestra pulled off this impressive rendition with a minimum of difficulty. The entire ensemble sounded on top of the composition’s demands. The women of the Symphony San Jose Chorale sang their part in “Neptune” with an otherworldly sheen, cutting off decisively in the final bar at Shimono’s direction rather than fading into the distance as the score directs.

Overall, this was one of SSJ’s finest hours, even more successful than its single courageous venture into Anton Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony a decade ago, one of Shimono’s previous highlights with the orchestra.

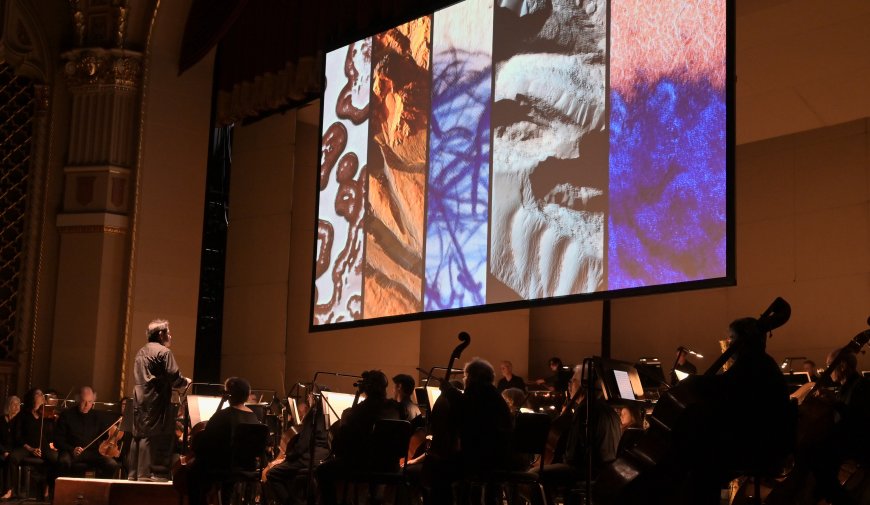

During Saturday’s performance, a screen lowered from the ceiling of the theater displayed an accompanying film titled The Planets: An HD Odyssey. Many of the shots of celestial objects appeared to be computer-generated. Others were so zoomed in it was hard to tell what they showed; certain images looked more like tree bark or microscopic photographs of viruses than planetary surfaces.

But the big problem with the film is that Holst was representing the planets’ astrological character, not their astronomical physicality, still less close-up views unavailable in his day. The movie, though impressive, appeared both incongruous and irrelevant. Fortunately, the orchestra’s performance was so lucid and compelling that the music remained the focus of attention.

The other works on the program rounded out the astronomical theme. Starburst by Jessie Montgomery is a short, bustling, and astringent piece for strings. The playing here was as crisp and vigorous as in Holst’s suite. The only ensemble issue — a common one in performances of this score — occurred when the cellos, carrying the theme, were drowned out by repeated slashes from the upper strings.

Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 in C Major got its nickname of “Jupiter” from the London impresario Johann Peter Salomon, who presumably found something reminiscent of the Roman god in this music, possibly its grandeur and majesty or perhaps the thunderbolt effect of its opening chords.

Shimono conducted with firmness and drive and — in the Andante cantabile — notable elegance. The orchestra’s tone and phrasing were dry and stately. Mozart’s “Jupiter” didn’t rumble or thunder as The Planets did, though this symphony can be performed that way, even with its much smaller orchestra.

One advantage of dry simplicity was a becoming clarity in the complex contrapuntal lines of the Molto allegro finale. They stood out audibly. Elsewhere, the small wind section was clear and piping, compelling attention. As a whole, this was a polite rendition worthy of respect rather than a performance eliciting awe or wonder. The amazement would have to wait until the second half.