The principal theme of the 2025 Carmel Bach Festival was “Dialogues,” with J.S. Bach’s The Art of Fugue as a running subtext through many of the chamber concerts.

Look a little further into the festival, though, and a stealthier theme becomes evident — the presence of women composers. Indeed, the Candlelight Concert on Sunday night, July 13 — named for the candles lining the side walls of the All Saints’ Episcopal Church where it took place — was devoted almost entirely to women, as advertised in the event’s title, “Ahead of Her Time.”

More or less familiar names appeared on this program. Clara Schumann’s Three Romances for Violin and Piano are basically salon pieces, not too substantial. Contemporary composer Jessie Montgomery was represented by her Rhapsody No. 1 for solo violin, which has an opening full of double-stops, builds to a crescendo of arpeggios, and ends pensively.

But then came Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel’s magnificent Piano Trio in D Minor, where two well-conceived, Romantic, turbulent movements surround a beautiful Andante espressivo and an Allegretto movement subtitled “Lied.” This piece, her last, is as good as her brother Felix’s own Piano Trio in D Minor. Ultimately, though, an interloping bit from The Art of Fugue — No. 17. Canon alla Decima Contrapunto alla Terza, in a transcription for violin and cello — sounded more modern than any of the 19th-century pieces on the program. The expert trio on hand consisted of violinist Gabrielle Wunsch, cellist Paul Rhodes, and pianist Lisa Edwards.

A string quartet concert at All Saints’ on Tuesday afternoon, July 15, “Timeless Inspirations,” led off with a generically classical period-style string quartet from 1769, by Maddalena Lombardini, who was a product of the Venetian orphanage music training system. From our time, Linda Catlin Smith’s As you pass a reflective surface passed the time with dissonant, sustained, quiet yet disquieting passages just this side of minimalism.

The “dialogues” began with Joseph Haydn’s String Quartet Op. 9, No. 2, whose morose third-movement theme is recalled in the Funeral March from Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, which itself is echoed in Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen. The opening movement of Mozart’s early String Quartet No. 13, K. 173 had much the same tune right off the bat. I couldn’t help but irreverently wonder whether this was dialogue or plagiarism or simple coincidence? Cynthia Roberts and Patricia Ahern (violins), Patrick Jordan (viola and author of the fine set of program notes), and Eva Lymenstull (cello) used period instruments that occasionally managed to stay in tune in the moist, cool Carmel climate.

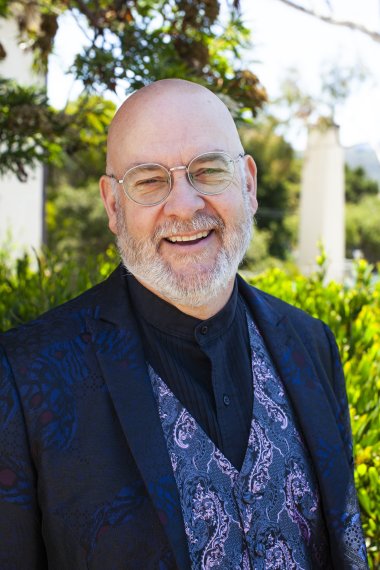

Artistic Advisor and Director of Choral Activities Andrew Megill, a fixture at Carmel Bach since 2008, had splendid ideas of his own, revealed at the Sunset Center on Tuesday night, July 15. For a start, he placed the Festival Orchestra off on the left side of the stage and the Festival Chorale facing the players on the right side, with the resident vocal quartet of Clara Rottsolk (soprano), Guadalupe Paz (mezzo-soprano), Brian Giebler (tenor), and Dashon Burton (bass-baritone) seated in a quarter-circle to the right of the podium. The arrangement fostered an amazingly even balance between the instruments and voices and made it easier for Megill to give cues. As alert as they had previously been for Artistic Director Grete Pedersen, the chorus and orchestra provided extra jolts of electricity for Megill in a mostly Mozart program.

After a lively rendition of Mozart’s rare Vesperae solennes de confessore (Solemn Vespers service), K. 339, Megill performed some daring surgery on Mozart’s unfinished Requiem K. 626, addressing misgivings that many of us have about Franz Xaver Sussmayr’s routine-sounding completion of the work.

Instead of using Sussmayr’s Sanctus, Megill inserted a Sanctus from the Mass No. 3 (early 1760s) by Viennese composer Marianne von Martinez, a classical-style movement that slipped by almost unnoticed. You couldn’t say the same about the music after Sussmayr’s Lux aeterna. Rather than end the Requiem right there, Megill went on without a pause into Latvian composer Peteris Vasks’s calm, tintinnabulating, layered, spiritually beautiful Dona Nobis Pacem — 13 minutes of sustained wonder in the “holy minimalist” manner that made Arvo Pärt famous in the West. It really worked, replacing Sussmayr’s forgettable music with something that lingered in the soul for hours. Now that’s a dialogue, even if it's an artificial one cooked up by an imaginative 21st-century choirmaster.

Megill returned to action the following evening, July 16, for the traditional Carmel Mission Sanctuary choral concert. The performance always begins with a ritual procession by the singers and attendants into the sanctuary and ends with a recessional. I found it anachronistically amusing to see several of the choristers reading their music from digital tablets as they marched in.

The musical menu was a bewilderingly diverse sequence of mostly a cappella choral pieces from William Byrd and Gregorio Allegri on the early end and James MacMillan and the late Steven Stucky on the contemporary end. Dialogues spanning centuries prevailed, such as paired Misereres by Allegri and MacMillan, or settings of “Komm, Jesu, Komm” by J.S. Bach and Sweden’s Sven-David Sandström. The chorus sang a Kyrie plainchant on the way in and Lou Harrison’s sonically matching Kyrie from his Mass for Saint Cecilia’s Day on the way out.

Carmel Bach 2025 continues through this week, culminating in the annual “Best of the Fest” concert at Sunset Center July 26.