Some composers and film directors are sewn together in our minds, stitched at the hip to form a conjoined cinematic twin. Hitchcock and Herrmann. Fellini and Rota. Spielberg and Williams. These two-headed creators forged a singular aesthetic, and neither party could have pulled it off without the other.

Forty years ago, Pee-wee’s Big Adventure unleashed the new mad lab experiment of composer Danny Elfman (b. 1953) and director Tim Burton (b. 1958). Both were weirdos from Southern California. Elfman grew up in Baldwin Hills, Burton in the Valley burbs of Burbank. Their artistic marriage was arranged by the late Paul Reubens, but there was instant chemistry. They shared a mischievous taste for the macabre, an affinity for outcasts and freaks, and a big, bleeding heart for romance, operatic emotion, and melody.

Eighteen films later — including such pop culture landmarks as Batman, Beetlejuice, and The Nightmare Before Christmas — their collaboration is being celebrated by the San Francisco Symphony on November 13 and 14, in a concert of many of their musical tricks and treats. Sarah Hicks will conduct the orchestra and Jenny Wong will prepare the San Francisco Symphony Chorus.

“Being able to work on Tim’s films for 40 years has just been such a great thing,” said Elfman. “And still, after all this time, he’s the least predictable director I work with.”

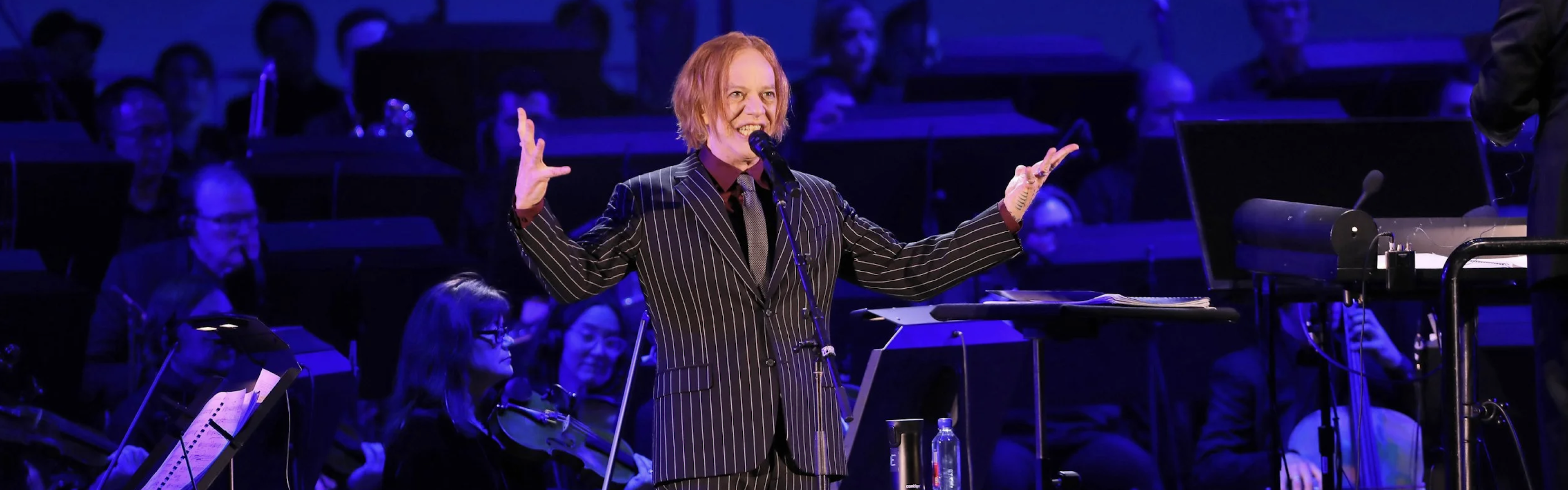

As he has done many times for the past decade, Elfman will reprise his singing role as Jack Skellington, the “Pumpkin King” protagonist of Nightmare Before Christmas — now a holiday classic.

The concert “Danny Elfman’s Music from the Films of Tim Burton” was first conceived back in 2013 and premiered at London’s Royal Albert Hall. It has been performed nearly 100 times since, in many cities and countries. The content has remained the same — Elfman arranged the 15 suites with his longtime orchestrator, Steve Bartek — although the composer has recently added a suite from the popular Netflix series, Wednesday.

Elfman has scored three feature films for Burton since the concert was first created, including last year’s Beetlejuice Beetlejuice. “The problem is this,” he explained, “anything I add now, I have to take something out, because it is simply the length that is affordable onstage with a symphony orchestra [given] the reality of union rules.” (He subbed out a Planet of the Apes suite to make room for Wednesday.) Realistically, though, more people are coming to hear Edward Scissorhands than, say, a suite from Burton’s 2019 remake of Dumbo.

The concert represents not only a staggering body of work by these two artists, but a vindication of their staying power. The movies have outlived many of their doubters and haters. Elfman spent his first decade as a film composer hearing — mostly from fellow film musicians — that he wasn’t a real composer and didn’t write his own music. (He is not classically trained and originally fronted the new wave band, Oingo Boingo.)

Their vitriol fueled his work. “There was a little bit of attitude that [I shook off] just from being around for the punk era, and that sense of ‘I don’t care about criticism from those who supposedly are much smarter than me, or know more than me, or have better taste than me,’” Elfman said.

For Elfman, Burton has been the perfect ally — another punk creative who was too strange for the Disney company, where he started out as an animator. Both were completely fearless, Elfman recalled.

“In the early days, I really didn’t care if I had a career as a film composer or not. [I thought] ‘I’ve got nothing to lose, because I’ve got a day job,’” Elfman said. “When I wrote the score for Pee-wee's Big Adventure, I fully expected Warner Bros. to throw it out — and I just didn’t care. It was like: ‘Tim is into it, and that’s all that matters to me.’ Really getting the director excited about a score is all I can ever hope for. But it was a weird score, and I thought Warner Bros. would hear it and go, ‘Let’s hire a professional, please.’”

“There was a lot of freedom back then,” he added, “in the sense that there wasn’t a lot of pressure from the studios to hear stuff. I didn’t even have to do presentations, frequently — on Beetlejuice, on Edwards Scissorhands, on Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, on Nightmare Before Christmas — I didn't have to play anything for anybody. Nobody was really paying attention,” he laughed. “And in hindsight, I realize what a luxury that was.”

Pee-wee was, among other things, an homage to Nino Rota’s circus-like music for Fellini films of the 1960s. It set the stage for the zanier passages in Burton films to come, but it also belied Elfman’s gargantuan ambitions and his growth as a composer for orchestra. Each score got a little bigger and more dramatic, crescendoing into gothic opera in Batman and a brumal fairytale ballet for Edward Scissorhands.

Nightmare was another vindication for the duo. A years-long passion project for Elfman, who wrote all of the songs in addition to providing Jack’s singing voice, it was dead on arrival at the box office in October 1993, though many critics liked it. Over the years, a new audience found it on cable and home video, and it is now a Halloween-Christmas perennial — not to mention a merchandising machine for Disney, which every year transforms the Haunted Mansion attraction in their parks to a Nightmare theme.

“That was the one that kind of broke my heart, because I put so much effort into it, and it was so misunderstood when it came out,” said Elfman. “The victory for me on that movie is that it’s something that has transcended generations, and new kids get into it. I always knew that it had the power to reach a very young audience.”

Elfman kept pushing himself — he’s justly proud of the rustic Americana tone poem he composed for Big Fish in 2003 — and now he has written multiple large-scale concert works. (Currently he’s composing a trumpet concerto.) In many ways, he has outgrown the wacky Burton aesthetic: his lilting, melancholic score for Milk (directed by Gus Van Sant) and his brutalist espionage music for the first Mission: Impossible (directed by Brian De Palma) are among his best work. He has proven himself to be a wide-ranging, ever-evolving artist.

But the Burton films will be his most recognizable legacy. Together they forged a world of delightful weirdness, of oddities who seance with the dead, fight crime while dressed like a bat, and kidnap Santa Claus and terrify children on Christmas Eve. Their films have a look and a sound that is totally distinct, perfectly Burtonelfmanian.

“I will go as far as he will let me,” Elfman said. “I’ve always been grateful that Tim gave me a very long leash. Because some directors, you can still do good work for them, but you just can’t wander far from where their expectations are.”

And yet, Elfman said he’s still nervous every time he demos a new score idea for Burton.

“I’ve done the most films, by far, with Tim, but I never know how he’s going to react to a piece of music,” Elfman said. “I’ll be working up a piece of music and I go: ‘man, I hope he likes this.’ So, in a weird way, it’s the same now as it was 18 films ago. He’s a totally unique personality, and even after 40 years, very unpredictable for me. But that’s good. It keeps me on my toes.”