The following is an excerpt from John Williams: A Composer’s Life by Tim Greiving. Published by Oxford University Press (copyright ©2025, all rights reserved), this is the first biography to detail the great American composer of the cinema age.

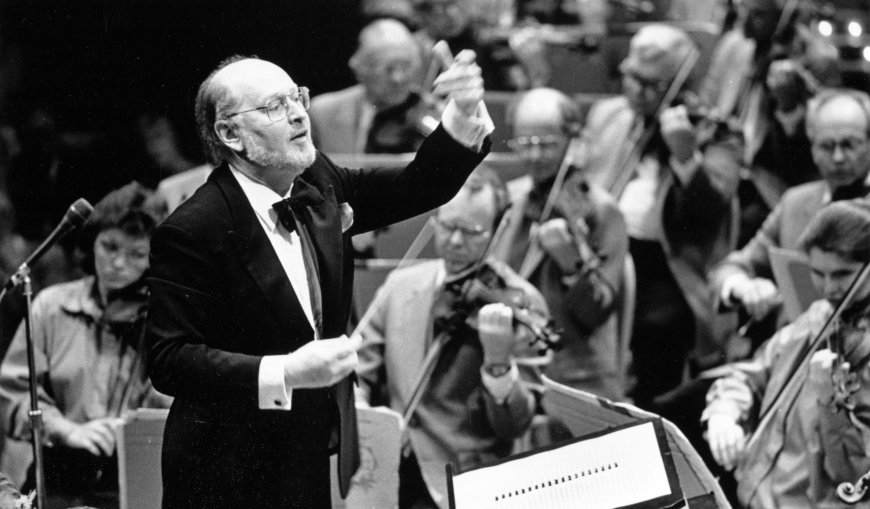

John Williams’s appointment as music director of the Boston Pops Orchestra was a national event. He was interviewed, profiled, and analyzed by dozens of publications, becoming a visible celebrity overnight.

Most people wanted to know why — why a hotshot Hollywood composer in the prime of his career would want to spend almost every night of his summer conducting light classical music. In his first press conference, John answered: “This is an opportunity to make music on a level I haven’t had before. The art of music for me has been a life-long love affair, a real passion, for more than 40 years. I know only a fraction of what exists, and my excitement now is that I have the instrument for exploring what there is more fully. You could say my position is ideal.” He kept referring to the Pops as an “instrument,” and he also compared it to a Rolls-Royce: “You feel responsiveness, reserves of power and energy. They can increase volume without having the tune get noisy. They haven’t got a vulgar sound in their whole repertory.”

Conductor/composer André Previn, who had worked in Hollywood himself, was his usual feisty self, explaining why he thought it was a great idea:

Anybody who thinks John Williams is “just a Hollywood musician” is completely wrong. He is such a good musician, so thorough, so completely schooled. John is damned fortunate at this stage of his career that the job at the Pops should be open. As I said to him recently, “Why do you want to spend the rest of your life in a frightening goddamn city like Los Angeles? You’ve got nothing left to prove out there.” At the same time the Pops is lucky that John is available. He is a first- class pianist, and he knows a terrific amount of music. Furthermore, he knows the orchestra from the point of view of the man with the pencil, and that means intimately. He can make superlative arrangements of pop materials, and he can edit, fix, handle anything that comes up in someone else’s arrangement, make it better, and all in a matter of minutes. That’s quite rare among conductors. Did I say rare? That’s being polite. It’s unique. He is also a very efficient conductor; the players of the London Symphony Orchestra, who have recorded several film scores with him, are full of admiration. They say there’s no nonsense about him, that he knows what he wants and he knows how to get it.”

Williams later admitted he took the job, in great part, “because André wanted me to be a conductor. Silly reason.” But John was also adamant that he was not following Previn’s path out of Hollywood in exchange for a career as an important maestro. “I leave that to André,” he said. “If I had his talent, I might consider it. But truthfully, I love film work. For me it is really fun.” This was purely a chance for John to stretch himself even more as a musician, a chance to dive into the library of classical music and go swimming, a chance to “invigorate my composing,” he said. It was a challenge to himself, to see if he had what it took to be like his friends Previn and Leonard Slatkin. It was an opportunity to step away from the writing desk and his hermit’s cave, and to play and exercise with other musicians for a few weeks every year. It was a homecoming to the town where his parents met, to the hall his grandfather helped build and where his mother grew up just a few blocks away.

On some level, he also saw it as a chance to evangelize the art of film music, and to persuade a classical audience in Boston — and across the United States, thanks to the nationally syndicated TV show Evening at Pops on PBS — to take that music and its composers seriously:

I find it disappointing that some of the greatest musical minds of the century have shied away from film music. When you consider the kind of audience you can reach, the sheer numbers of people, it’s a shame that Stravinsky, for example, never wrote film music. I say this with complete awareness of the dangers of easy popularization. Prokofiev wrote splendid music for films, and it never endangered his art. There’s commercialization in a healthy sense as well as an unhealthy sense. Maybe that’s why I find the Boston Pops programming idea congenial. A lot of it is light and fluffy, but some of it is the best music there is. The same audience digests it all to one degree or another. It shows what can be done in a popular forum.

He suggested that it was possible for him to “bring prestige to the best film music by presenting it in a concert format. Only one half of one percent of the music written in the 19th century is anything we ever hear today; surely there must be at least that percentage of good music written for films.”

In 1980, the wall separating the concert hall and film music was impossibly high and barb-wired at the top. The only way to get it into Symphony Hall was to remove the serious leather seats and serve it with sandwiches and beer. It was all right for the Hollywood Bowl and those Filmharmonic evenings, but when Williams dared to take it inside the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion with the Los Angeles Philharmonic or any other “serious” venue, he was met with fangs among the appointed tastemakers and gatekeepers. When he conducted the Pops in Detroit that February, the Free Press critic sneered: “His compositional style ranges from Copland mimicry…through pompous, brassy open fourths and fifths (Superman and Star Wars) to weak imitations of the contemporary Hungarian composer Gyorgy Ligeti (Close Encounters of the Third Kind). While it may suit the films it accompanies, it can’t stand on its own too well.” A pops orchestra was the only viable option for making a concerted effort at programming film music in the hall — and even then it had to contend with clinking silverware and noisy chatter. That was one of the hardest things for John to get used to: “People told me I waited too long between numbers. I kept waiting for the din from the audience to die down, but it never did.”

When the concept was first introduced, “pops” simply referred to light classical music —overtures, waltzes, marches, and pleasant symphony movements. In time, the category grew to embrace Broadway show tunes and later the orchestral — or big band — music that was popular in nightclubs and on the radio. Before the 1960s, most pop music was orchestral. But Arthur Fiedler, the longtime Boston Pops music director who had preceded Williams, didn’t draw a line when the radio started to fill with rock ‘n’ roll: he commissioned orchestral arrangements of Beatles tunes and invited Karen Carpenter to sing with the Pops. Williams made the irrefutable case that, of all things, movie scores were the organic inheritor of the “pops” mantle: orchestral music, fun and emotional and catchy, heard by millions of people around the world.

For the most part, Williams was welcomed with open arms by Boston and the BSO, who were excited to have such a starry yet modest celebrity at the helm. Only a tiny minority of naysayers spoke up when his hiring was announced. “Williams made no impression on me whatsoever,” said Jordan Whitelaw, producer of Evening at Symphony — the “serious” counterpart to Evening at Pops. “His music shouldn’t happen to a dog. I don’t think anyone in the orchestra could have conceived that he would have been named conductor. So, mazel tov.” One anonymous violinist said of Williams’s tryout: “He didn’t make a strong impression. He seemed a relatively unremarkable conductor. It seemed obvious there were other reasons why he was at the Pops.”

Jenny Williams, his daughter, who was now 23 and in premed school at USC, later said it was “very, very brave to do something like that in the middle of his career, and also have to deal with understanding the minutia and workings of the Brahmin Boston crowd.” And while the embrace was an overall warm one, John had an uphill battle ahead. The musicians had grown complacent and bored under Fiedler. They were contractually forced to play the Pops summer season, and many did not hide that they were there under duress. They were used to performing the same old tired music, much of which they neither respected nor enjoyed. And now here comes Mr. Hollywood, with almost no public conducting experience, bringing in a stack of movie music. There was a pool of low-level discontent that would bubble for a few years…and eventually boil over.

But despite some rough patches along the way and a near end to the relationship in 1984, Williams’s tenure with the Pops was a massive success — for 13 seasons he conducted more than 300 concerts, did multiple tours (including to Japan), recorded more than 20 best-selling albums with the Pops, and brought in countless new orchestra listeners both in Boston and across the country. His time in Boston is what really turned him into a concert conductor, which would eventually take him all the way to the halls of Berlin and Vienna. But perhaps the greatest legacy, and the biggest success, is that Williams used his position at the Pops as an instrument to break down the divider between film music and the places of “high art.” As conductor of the Boston Pops, he accomplished his mission of elevating the best that film music has to offer, gradually winning over audiences, musicians, other conductors — and even a few critics.