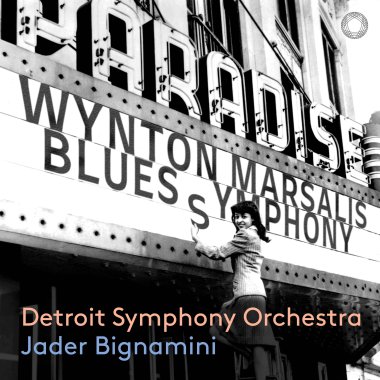

The ever-prolific trumpeter and composer Wynton Marsalis often thinks big when he writes for orchestras, seemingly subscribing to Gustav Mahler’s credo that a symphony should embrace the entire world. And Jader Bignamini, music director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra since 2020, thinks likewise. In restarting the DSO’s recording agenda, Bignamini is leading off with one of Marsalis’s mammoth concoctions, the Blues Symphony (Pentatone).

The piece, dating from 2009, isn’t brand-new, nor is this its first recording: Cristian Măcelaru and The Philadelphia Orchestra put out a digital release four years ago on Blue Engine Records, the in-house label for Jazz at Lincoln Center, where Marsalis is managing and artistic director. But the Detroit performance is the first to be issued on physical CDs.

As is typical of Marsalis’s four “symphonies” (they’re more like suites), this work is outsized in length (just over an hour), expanded in structure (seven movements), and omnivorous in its mission to include just about every influence that its composer has ever acknowledged. The score is sort of a pocket history of jazz dressed up in symphonic garb, with the traditional 12-bar blues sequence (used in thousands of songs and jams) running as an undercurrent through much of the piece. Wynton being Wynton, the Blues Symphony stops short of developments in jazz around 1965 or so.

The opening section, “Born in Hope,” begins with a fife-and-drum intro, marching from silence into the concert hall, as it were. Soon, the 12-bar blues gradually emerges, and the orchestra starts to work out the sequence, getting louder and rowdier before the parade passes out of earshot. The blues structures in “Swimming in Sorrow” are fainter, but they’re there if you listen hard. The DSO winds and brass freely wail within the confines of Marsalis’s writing, the clarinet glissandos harkening back to the famous first measures of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue.

“Reconstruction Rag” opens with fractured ragtime syncopations giving way to New Orleans contrapuntal maneuvers and orchestral bombast. “Southwestern Shakedown” starts out coyly before the blues rears its head — the loping rhythms evoking cowboys, a train — and there are dizzying string passages that the DSO handles pretty well. The group even swings.

“Big City Breaks” adopts a tough, broken-up swing rhythm, with dizzying swirls in the trumpet section this time. The sixth movement incorporates the Latin American element — what pianist Jelly Roll Morton called the “Spanish tinge” — starting with a deliberately paced Cuban danzón, joined by a full-blast mambo, and concluding with a complicated scherzo-like Brazilian samba. The finale scampers around like mad, this “Dialogue in Democracy” gone berserk, interrupted by discordant screams before the running pace restarts.

Bignamini succeeds in showcasing the DSO’s agility, versatility, and fire with this difficult, ceaselessly eclectic piece. Together, they make a spirited case for what Marsalis now calls his Symphony No. 2, just another notch in a belt that, along with his other symphonies, is said to include three concertos, 11 ballets, 13 suites, and — would you believe — 600 songs. Given this and all of his other performing, educational, and administrative activities, Marsalis’s work ethic is beyond incredible.