The nation is tense, and California’s Central Valley farm fields have become an unlikely flash point. The workers — mostly immigrants — who harvest the fruits and vegetables that feed much of the country are scared and angry. They labor to the point of physical exhaustion for low pay. Protests against these conditions are organized and soon gain widespread support.

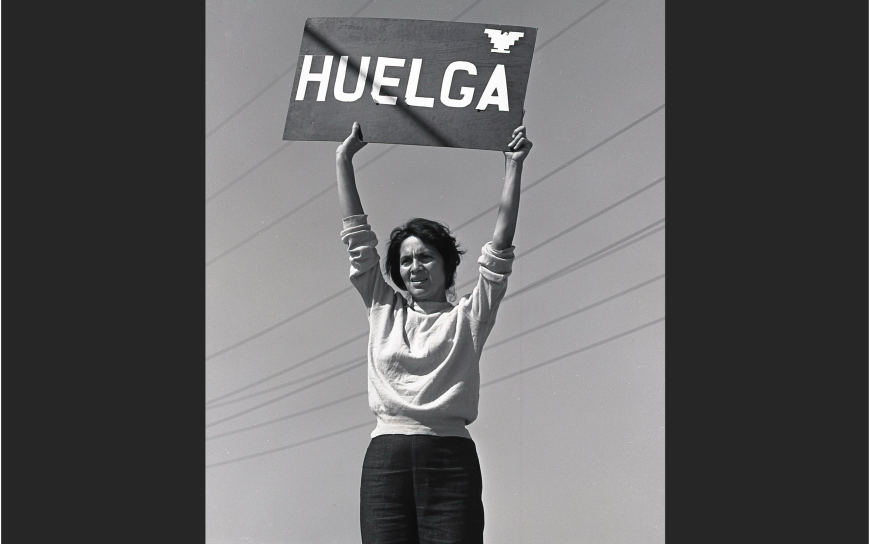

This may sound like a dispatch from the front lines of 2025, a year that’s been marked by the Trump administration’s immigration raids and arrests across the state’s agricultural industry. But it’s also the historical backdrop for Dolores Huerta, who in the mid-1960s spearheaded a nationwide boycott of table grapes in solidarity with striking farmworkers. Alongside fellow labor leaders Cesar Chavez and Larry Itliong, she played an integral role in the era’s civil rights movement.

Huerta’s story is a dramatic tale of friction and solidarity, of hope lost and restored — big themes practically made for the operatic stage. And that’s exactly where they’ll land on Aug. 2, when West Edge Opera presents the world premiere of Dolores.

The East Bay company will feature the new opera as one of three productions in repertory during its summer season at Oakland’s Scottish Rite Center, along with Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s David and Jonathan and Alban Berg’s Wozzeck in performances through Aug. 17.

In development for five years, Dolores is not a direct reaction to today’s tensions. But it’s hard to imagine a better time to recount how a previous generation of immigrant workers stood up for their rights.

“It’s funny how you can make plans to do something, and it suddenly, magically, seems very appropriate for the times,” West Edge General Director Mark Streshinsky mused from his office in Berkeley.

Huerta’s name was a familiar one for Streshinsky growing up. His father Ted Streshinsky — a prominent photojournalist whose work appeared in Time, Life, Look, and other magazines — covered the early days of the grape boycott. Honoring that family legacy, the director is using some of his dad’s images in the production.

But composer Nicolás Lell Benavides has even stronger ties to this history. Huerta, who is still active today at age 95, is his third cousin.

“She has jokingly introduced me as her grandson,” said Benavides, a New Mexico native who spoke from his home in Long Beach. “I knew her as a kid. She would frequently be at big family reunions we’d have in El Paso. She was present and attentive, particularly to children.”

Benavides and librettist Marella Martin Koch pitched the idea for Dolores in 2020 through West Edge’s Aperture program, a pandemic-era initiative to incubate new operatic works. The pair’s proposal stood out in a competitive field and was awarded a full commission the following year.

Early in the writing process, Benavides and Martin Koch decided to focus the opera’s action on a pivotal few weeks in the summer of 1968, when the farmworkers’ strike was buoyed by the support of U.S. senator and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy — and then dealt a huge blow when he was assassinated. Huerta was with Kennedy at Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel the night he was gunned down.

“I wanted to show what it felt like to deal with such high stakes, to go through such immense loss, and to discover the light on the other side,” Benavides explained. “A lot of ancient mythological stories are built that way — where heroes go through trials, emerge victorious, and teach us something about resolve.”

Huerta’s story has an added advantage, the composer noted. “I think it’s easier to see ourselves reflected in real people and see that it’s possible to do something heroic.”

The opera is largely true to the historical record, taking only minor liberties with the timeline of events and, out of necessity, imagining the intense conversations between Huerta and Chavez as they debated the best way forward.

“Leadership isn’t this unified, dreamy state where everyone knows what to do and how to do it,” Benavides said of the opera’s realist approach. “There’s a lot of doubt, a lot of mulling over decisions, a lot of discussions of how best to use finite resources and manpower. To me, that’s a really interesting aspect of the story. They were refining their skills as leaders.”

Benavides has seen his own career take off in recent years, graduating with his doctorate from the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music in 2022 and receiving a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in 2024.

His score for Dolores is “exciting, driving, and definitely connected to the culture of chant and protest,” Streshinsky said. It’s also eclectic, drawing on genres that range from traditional Mexican ranchera and corrido to musical minimalism and even Gregorian chant. Saxophone and electric guitar augment the opera’s otherwise standard classical chamber orchestra.

Benavides likewise communicates a great deal in his writing for singers.

“I wanted the politicians to have high voices so they would kind of float above people,” he said, describing how he’s cast the characters of both Kennedy and Richard Nixon as tenors. “Even well-intentioned politicians can’t always connect with working-class people. Dolores and Cesar are lower voices, more connected to the earth.”

Capturing that earthiness has been a goal for mezzo-soprano Kelly Guerra, who’s set to play the title role of Huerta. To fully reflect the real-life activist, whom the singer met at a public workshop production two years ago, “I have to remember to be welcoming and joyful — not just righteous,” Guerra said, from her temporary residence in El Cerrito.

“It’s an honor and a joy to help your community,” added the singer, who first heard of Benavides when they were both students at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

Huerta, a lover of the arts, plans to attend opening night. Throughout the work’s long development process, “she has been very supportive but very hands-off,” Benavides reported. “She said, ‘I trust you to do a good job.’”

That faith is being rewarded with growing interest well beyond the Bay Area.

“Friends at other companies started calling me, saying they were hearing about it and were interested in being co-producers,” Streshinsky said.

As a result, the piece plans to hit the road following its East Bay premiere. Dolores travels to Opera Southwest in Albuquerque in October and is slated to appear in future seasons at San Diego Opera and Santa Monica’s BroadStage.

By that point, the political conversation will undoubtedly have shifted. But the opera’s creators believe their themes will continue to resonate.

“There are parallels today — and inevitably, there will be parallels 50 years from now,” Benavides said.

“I’m not foolish enough to think an opera can change the course of politics in the United States,” he added. “But making art that speaks to our current condition is a magnificent way to process what we’re all thinking about.”

This story was first published in Datebook in partnership with the San Francisco Chronicle.