If you ask why a young Black man would adopt the stage name Taj Mahal back in the late 1950s, you will find the inception of a lifeline of reverence and seeking. Born Henry St. Claire Fredericks Jr. and raised in western Massachusetts by parents from the Caribbean and South Carolina, the budding musician and aspiring farmer was influenced by his dreams of Mahatma Gandhi to connect to the Indian edifice associated with love.

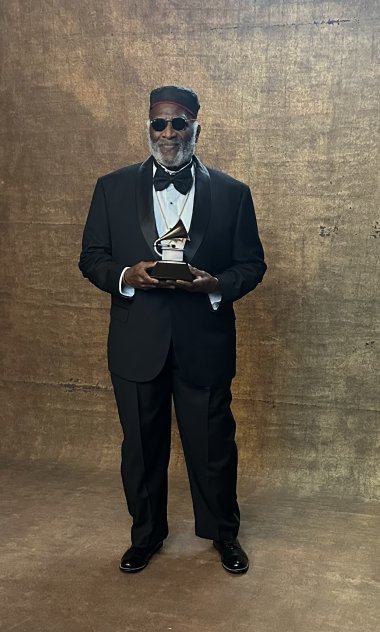

Now 83, Mahal has sustained a lifelong celebration of blues and other roots musics, shared in scores of recordings, played worldwide tours, and been featured in films and TV productions. His solo and collaborative explorations have garnered five Grammys, including a Best Traditional Blues Album award alongside a Lifetime Achievement Award earlier this year.

Mahal will be celebrated during a four-night stand at SFJAZZ next week, in the company of longtime acquaintance and bassist Bill Rich, Trinidadian drummer and folklorist Tony D, keyboardist Jim Pugh from the Robert Cray Band, and some surprise guests. The set list will be drawn in part from Mahal’s newest Concord album, Room on the Porch, a collaboration with friend and fellow bluesman Keb’ Mo’.

San Francisco Classical Voice sat down with the veteran multi-instrumentalist and singer at Subway Guitars in Berkeley, which he asserts is “one of the best stringed instrument stores in the United States” and located within walking distance of his home. Mahal conversed with the same ingenuous, gravelly warmth familiar from his decades of performance.

How much did your family have to do with setting your compass?

My father and my father’s father, from Saint Kitts, were [Marcus] Garveyites. And my folks steered me in the direction of Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington. And we lived like 12 miles away from Paul Robeson.

That says something about your politics, what about the music?

They both played piano, and my father made the kind of money at it that was able to keep him going before they got married and I and my sister came along. He got a factory job with Firestone Tires in Chicopee, Massachusetts, and we grew up in Springfield, which had really good schools.

I heard that your folks started you in on classical music, on several different instruments. Did you get training in school, too?

Some. I can remember being in grammar school and rearranging tunes like, “Oh! Susanna,” so I could swing it more like jazz and get another rhythm in it.

Where did your plans to be a farmer come from? Many of your fans don’t know about that.

My mother was from a farming family, and when my folks were taking us out to the country, I was feeling something out there — I wanted a farm. I got involved in the Future Farmers of America when I was in the tenth grade. After graduation, I spent a solid year-and-a-half or so on a farm to see if that kind of life was going to be what I really wanted to do.

Did the music stay with you?

I took a page out of my ancient African continental situation, which is, the music always inspires the life, it functions as a part of it. And when I flicked the switch on for the compressor to milk the cows in the morning, the radio came on. I was listening to everything from Marvin Gaye and Del Shannon to a lot of rhythm and blues.

Then you went on to the University of Massachusetts, in Amherst.

I majored in animal husbandry with a minor in veterinary science and agronomy and dairy technology. I saw that agriculture was moving toward mechanization, so I thought maybe I should see what they’re doing on that level, even though I wanted a more organic, traditional way of doing things. Things that we of African persuasion brought to the soil here in the United States.

You also studied ethnomusicology.

I’d grown up in an area with a diversified population. Everybody had their own kind of music, because many of the parents were immigrants, like my dad — Italians, Welsh, Poles, Armenians, Lebanese, and so forth. When I was a kid, fiddling with the radio, I punched in this incredible music that filled every single one of my molecules with golden liquid. It was a program called Hawaii Calls.

And you also wanted to make your own music.

When we first got to college, we were guys with a guitar, a mandolin, a banjo, and there were girls’ dorms with a walkway in between that was like a natural amphitheater. So the guys would get there and play and the girls would enjoy the music. We formed a band and played all around the Northeast. I was the secret ingredient, because I brought the R&B, and I also followed the style of Blind Willie Johnson, who’d played 12-string guitar more like it was ragtime piano.

Did you hold on to the dream of getting your own farm?

Agriculture swirls around my head every day, but I started farming music. Once I left school, I started playing in and around Boston in the coffee houses, trying to break into that scene. I was booked at Club 47 in Cambridge, where Ian & Sylvia and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Joseph Spence played, and I met Jesse Lee Kincaid there. He played some Reverend Gary Davis stuff, and I said, “where the hell did you learn how to play like that?” He said, “Well, when I was living in L.A., I took lessons from this guy named Ry.” So Jesse and I ended up making a duo.

And then you both headed out West.

At the end of ‘64. I needed to know who this boy Ry Cooder was, because as much as I was a singer, I wasn’t that much of a player of the music at that time. The industry is pretty big around you when you come West, but it’s all about focusing on what you need to be doing. It’s my integrity and who I am at the end of the day. It took me about five years to really let go of the pull of the East Coast and to be free in California.

Were you writing your own stuff?

I didn’t really start that until my first album [Taj Mahal, 1968, Columbia Records].

What moved you to Berkeley for the first time, in 1970?

Back when I was still on the East Coast, I’d seen the contemporary forward mindset of Mario Savio, and the politics and the youth movement. When I finally got to Berkeley, things really got a lot better.

How was it different from LA?

It was roots-driven, meaning that it wasn’t that plastic. I played with Jesse Ed Davis at the Avalon in San Francisco and at the Poppycock in Palo Alto, and pretty soon we were getting national tours and whatnot. [Guitarist and pianist Davis also appeared on Mahal’s first four albums.]

In 1981, you relocated to Kauai and got back to the Hawaiian music you’d discovered as a kid.

I met Carlos Andrade, who was a Hawaiian slack key guitar and ukulele player, but the guy he liked the most was Mississippi John Hurt, who was one of my mentors. Carlos and the members of his Na Pali band wanted to learn the blues turnaround [a transitional musical phrase] and I wanted to learn the Hawaiian turnaround. So we formed the Hula Blues Band and created a really nice sound.

Did that happen for you with other world musics?

Back in Boston I’d bought an album of Gambian kora music, and later I saw an article about it in Sing Out! magazine. People brought [Gambian griot] Alhaji Bai Konte to the United States, and I did a tour with him and [American blues veteran] Elizabeth Cotten. When I’d play Mississippi John Hurt’s “Take This Hammer,” Alhaji would pick it up before I was halfway through the phrases, because his music was the root of it all. I’ve done a whole album with those players; we’re honoring the African griot tradition.

The Los Cenzontles Cultural Arts Academy in San Pablo let me know that you’re in residence with them, alongside David Hidalgo, and that they’ll be releasing recordings with you, as well as a documentary with you and David available on their website later this month. What else do you have planned?

I’ll be headed to the studio later today, but I’m not at liberty to give out information on that. I can tell you I’ll have my band on two blues cruises, one in October and one in January. And that there’ll be new and rereleased albums by the Phantom Blues Band [comprised of stellar session players and sidemen]. And I’ll be doing a Sly Stone song at the Sound Summit tribute to him on Mount Tam, on September 13.

And I have one thing more I’d like to tell your readers: Jazz gives you back your mind, reggae gives you back your body, but the blues, the blues, the blues will give you back your soul. Right?