Programming little-known music is a gamble, but hearing it is also risky. First impressions are tricky, especially given how beliefs about epochs and styles shape how we hear things that don’t fit neatly within them.

The Ives Collective, performing at Noe Valley Ministry for the first time on Sunday, brought this tension to the surface in a concert containing two rare chamber pieces and Johannes Brahms’s Piano Quartet No. 1. Their more-than-capable performances showed both the importance of programming “new” music and how to do it creatively.

The two works date from the early 20th century, when musicians collided with modernism with chaotic results. This was the era of Arnold Schoenberg and serialism, early Soviet musical experiments, French Surrealism, jazz, and much more. Yet these familiar trajectories are broad, and they obscure many less easily categorized musicians. While cellist Stephen Harrison recounted “accidentally” discovering Jean Cras’s String Trio, its pairing with Leo Ornstein’s Cello Sonata No. 1 serves as a warning against easy generalizations.

Cras’s Trio provides a perfect example. While the careers of archetypal French composers Gabriel Fauré, Claude Debussy, and Maurice Ravel centered on the Paris Conservatory, Cras was at sea, literally. He was in the French navy at the start of the Great War, eventually rising to the rank of rear admiral. He had only a few months of musical training.

The Trio, written in 1926, captures bits of this biography. In the middle of the second movement, as Hrabba Atladottir’s violin sang a tortured, Breton-inflected song, the cello part conjured vivid, terrifying waves. Cras’s breadth of stylistic references only grew as the Trio went on, with an insistent, guitar-like plucking in the third movement reminiscent of Ravel’s String Quartet, and a jig in the finale that contrasted with a soft, lyrical second theme. No conservatory-trained modernist composer wrote like this, with such different styles casually packed together.

While the first movement seemed to promise a livelier version of a Haydn trio, by the end it was clear that this was neither classical nor modernist, indeed not one thing at all, but a piece drawing comfortably from different worlds. The result had a thrilling effect: unable to wait until the end, the audience burst into applause after the third movement’s virtuosic climax.

Leo Ornstein’s Cello Sonata No. 1 similarly dared to reimagine “modern” music, but via different means. Ornstein, a refugee from Russian pogroms, emerged as America’s most energized modernist, writing highly dissonant pieces with names like Suicide in an Airplane. Yet he reversed course with this sonata in 1918, referring to it as the “Romantic” response to his “ultra-modernist” music of the previous decade.

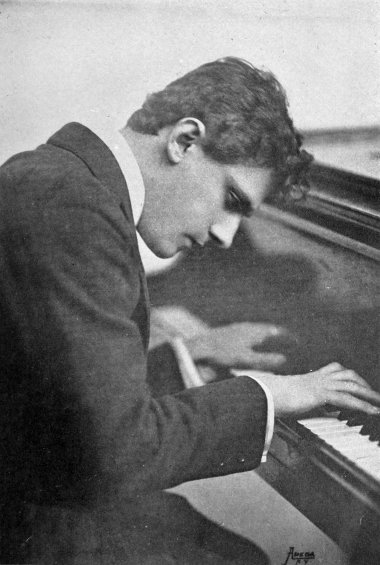

Even so, this story draws too neat a distinction, as the cello’s cantor-like singing in the second movement is accompanied by an eerie, machine-like pattern of chords whose colors I’d hesitate to attribute to any tradition. The section was made even more vibrant by pianist Keisuke Nakagoshi’s obvious ear for these sounds. The sonata thematizes this relationship between contrasting styles, especially in the following scherzo, in which the piano and cello are pitted against each other in a rhythmically disjointed yet still singing dance. Ornstein may have seen himself as reverting to 19th-century Romanticism, but this sonata is — like Cras’s Trio — a product of both past and present.

Harrison and Nakagoshi performed only these two inner movements of the four-movement sonata, likely to save time. My instinct was to complain about this excerpting, but then I wondered: How many new works and new composers might we discover if performers took the Ives Collective’s lead and programmed excerpts? In previous centuries, musicians and audiences were comfortable with cutting up movements, even of symphonies. Why limit ourselves by insisting otherwise? My only regret on Sunday was that the Ives Collective didn’t chop up the overstuffed Brahms Piano Quartet No. 1 — the best parts of which occasioned stellar solos by violist Susan Freier — in order to make more room for these thrilling “new” chamber works.