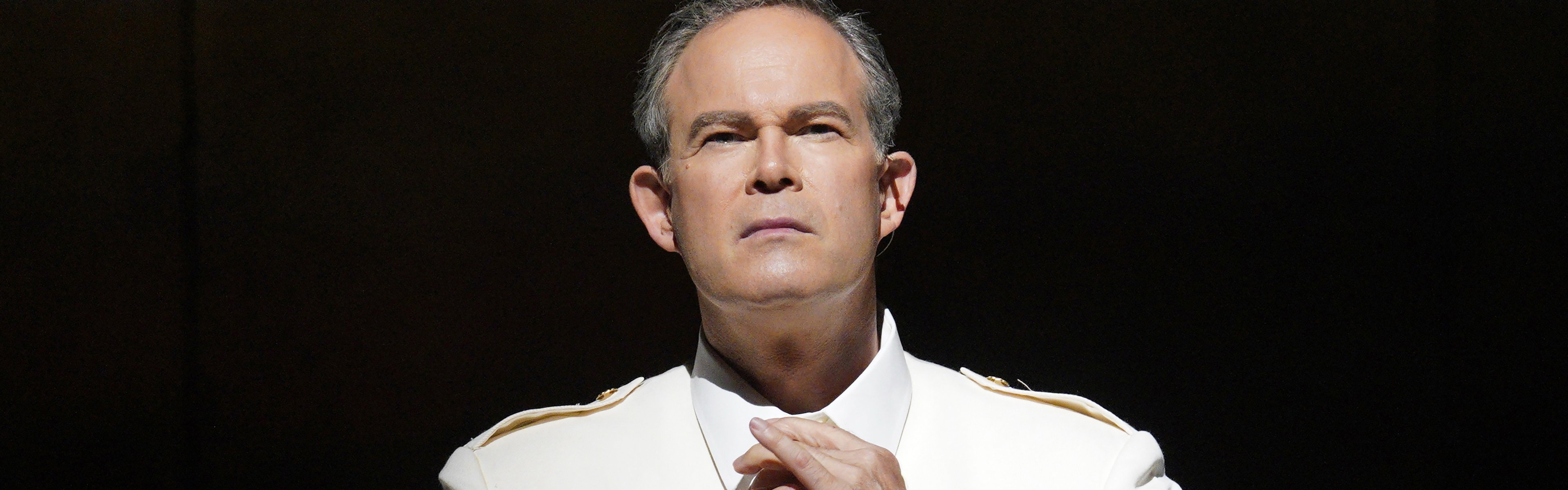

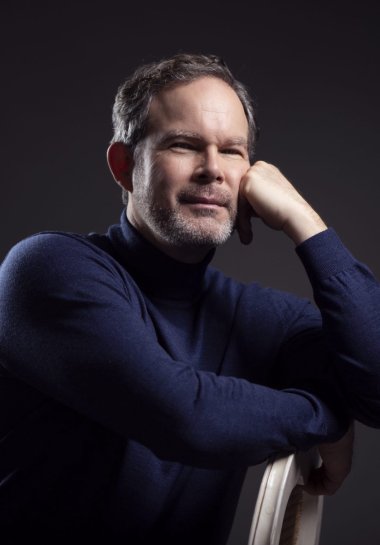

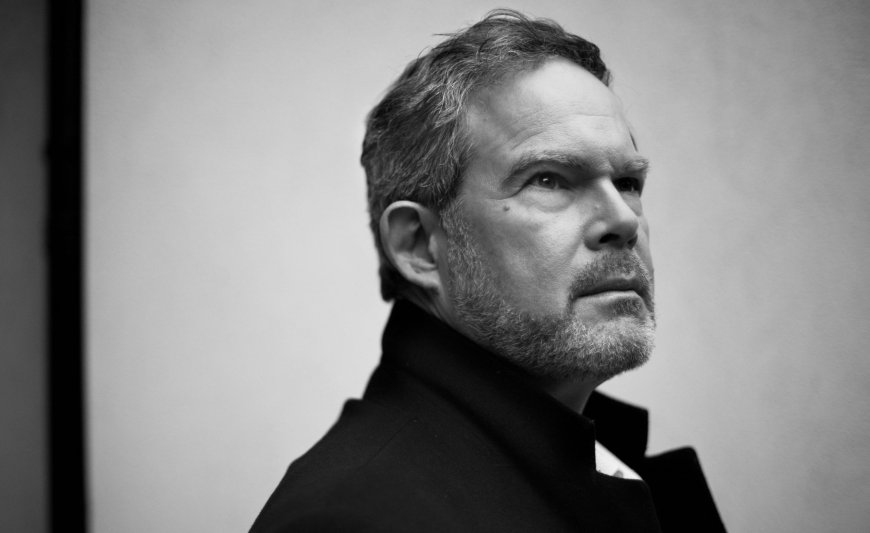

At 65, Grammy Award-winning bass-baritone Gerald Finley continues to electrify audiences around the globe. A leading singer and dramatic interpreter of his generation, he will be in recital at Santa Monica’s BroadStage on June 11, accompanied by pianist Bryan Wagorn.

Finley has put his indelible stamp on opera history by singing in many notable world premieres, from John Adams’s Doctor Atomic in 2005 to, most recently, Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Olivier Award-winning Festen this past February. So it’s only fitting that the Canadian bass-baritone should also be featured on a postage stamp in his home country, issued in 2017. (Seriously!)

Finley was born in Montreal and began singing as a chorister in Ottawa. Completing his musical studies in England, with a stint as a young artist at London’s National Opera Studio, he focused on Mozart in his early career, making his debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1998 as Papageno in The Magic Flute.

A regular at the Met since then, Finley has appeared in a dozen operas there, including Adams’s Antony and Cleopatra, which concludes its run this week. The work, with the role of Antony written for Finley, had its world premiere at San Francisco Opera in 2022 and has been yet another achievement in the bass-baritone’s ever-expanding contemporary repertory. An

other signature role is Jaufré Rudel in Kaija Saariaho’s L’Amour de loin, which he first sang in 2001 in Paris.

Complementing his concert and recital engagements, Finley’s many solo CD releases have been devoted to the songs of, among others, Samuel Barber, Benjamin Britten, and Henri Duparc. The bass-baritone’s collaborations with pianist Julius Drake have won several Gramophone Awards. In 2017, the singer was appointed a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

SF Classical Voice caught up with the uber-busy Finley on Zoom, with the discussion ranging from his love of contemporary music and his upcoming BroadStage recital to his affinity for playing nasty characters. This conversation has been edited for concision and clarity.

Was music a given in your family? Your father, a former boy chorister, sent you to St. Matthew’s Anglican Church in Ottawa when you were 10.

And here I am at the end of a long journey — which, as you say, began with the arrangement that my father had. His adoptive uncle, Sir William McKie, was the former organist of Westminster Abbey [in London]. Because there were a number of boy choirs in Ottawa, my father said, “Let’s have six weeks of it and see how you get on.” I didn’t even have any piece to audition with and had to sing the national anthem for goodness’s sake.

But I said to myself, “It has to be fun, [or] I’m not going to do this.” And from the moment I joined a bunch of rough-and-tumble fellow Canadian boys, it was not just about the singing. The music joined us together; the music was incredible. I never [thought] that being a singer in that environment would propel me forward through my teens, [but] eventually, I found myself thinking I could be a professional choir person. It all unfolded from there.

You’re about to finish the Met run of Antony and Cleopatra. Because you worked with Adams and director and librettist Peter Sellars on Doctor Atomic, did the composer just call you one day and say, “I’m writing Antony and Cleopatra”?

Yes, in fact, he did call me. The joy of working with a [living] composer is that we’re [experiencing] the same world events and circumstances. Having a perspective on what’s going on in the world through a composer is an unbelievable opportunity to reflect on artistically, as well as in day-to-day life.

My first encounter with Peter Sellars was [when I played] Papageno at Glyndebourne in 1990. It was his production, where Papageno didn’t have any words to speak at all, which was quite a controversial situation. You had to rely completely on your stage presence and the music you sang. [Over my career] Peter has guided me through a number of personal journeys, as well as artistic [ones]. It was through him that I joined L’Amour de loin, which also was an amazing journey with [soprano] Dawn Upshaw and Esa-Pekka Salonen, and we recorded it in Helsinki.

My first knowledge of Doctor Atomic was through Peter. I had met John only virtually, and he said he had listened to my recordings, and then I was in New York in early 2005. The first time I met John face-to-face was the first rehearsal of Doctor Atomic. He had come to a performance of Don Giovanni at the Met. [With Doctor Atomic] he realized, “Oops, I’ve written the part a little too high.” I said to him, “Your instincts are probably right for the role.” We worked together on it, and he allowed me to try some alternatives. In the end, of course, everything he wrote was the correct stuff, and we’ve gotten on famously ever since.

And a similar approach was taken with Antony and Cleopatra?

Yes, he said we could adjust [the score] as necessary, but again, he wrote the role perfectly for me. He’s reduced [it] very slightly, but mostly I’m singing the notes that he initially wrote.

You’ve said that there’s no line between the traditional and the contemporary for you. When did you first realize that you wanted to sing contemporary music?

I was introduced to contemporary music when I was still a choirboy. The friends of the choir director were excellent composers, and every Christmas we sang a new carol. I think because that became a normal part of what we did, it seemed natural that there should be new pieces along with the old. Of course, what we’re trying to do [as performers] is encourage composers to write the next traditional thing — that music that’s written today will continue to be heard in decades or centuries to come.

Every piece, at some point, was contemporary music. So when we hear the words “classical music,” [we may be talking] about things that were played 100, 200, or maybe 300 years ago, [but] it’s just music that’s been heard again and again because it’s been enjoyed by audiences over those many years. Now we just have to keep encouraging those wonderful composers like John Adams, like George Benjamin, like my friend Mark-Anthony Turnage, to create works that speak to our time, that may speak to the future and certainly speak of the past.

Let’s talk about your upcoming recital. First, what makes a good program, and how did you decide on the repertoire?

As a recitalist, I’m after my own artistic exploration. I may concentrate on a poet or a composer to examine — to do a bit of surveying, shall we say, of their work. There was a tendency in the latter part of the last century, the 1980s and ’90s, to go for a theme — love and death or the seasons or the color green — and build a program around that. I’ve gone through that process, [but] I’ve learned that, in the end, what’s really worthwhile programming is the music that I love to sing and the music that I feel is good to share with the audience.

And that’s a tricky situation these days. Of course, I want to give opportunities to contemporary composers and poets to be part of the recital platform. I always look at new music and see if I react to it in a positive way and think, ‘Yes, this deserves to be sung.’ In some ways, I’m trying to reveal my love, to reveal my personality, to reveal my enjoyment of singing and the strength of the music that’s available.

You’re also singing in five languages, including works by Barber, Edvard Grieg, Maurice Ravel, and Richard Wagner.

It’s ridiculous, isn’t it? For BroadStage, particularly since it’s my first visit to the Los Angeles area as a recitalist, I wanted to give something which was a broad sweep of my repertoire. It’s a mixture of song and opera [because] I don’t think I would be doing anyone any favors if I didn’t sing a bit of my favorite arias.

I’m happy to explore and share the beauties of the Russian song repertoire — Sergei Rachmaninoff’s “Spring Waters.” And [then there’s] French with Ravel [Don Quichotte à Dulcinée], Italian with Verdi [Iago’s “Credo” from Otello], and of course, the English folk song element, as well as German lieder.

You’re also known for singing some very nasty — or flawed — characters: Iago or Scarpia in Tosca, for example. What’s the allure?

It’s the kind of thing where I’ve tried to tell my mother, [who’s] celebrating her 100th birthday this year, “I’m only that onstage!” Creating drama, plot, tension, emotional dynamics onstage, there has to be a force somehow — the evil, unfortunate side of human nature which seeks power and invests in cruelty. Without those, we can’t fight for good.

Characters like Iago or Scarpia have their demonic angles. Nick Shadow in Igor Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress can be also demanding, [as can] playing Mephistopheles in various versions of Faust. These are all characters which need to be played with commitment, with seriousness.

Roles I’ve been playing more recently — Antony, Oppenheimer [in Doctor Atomic], or even [Verdi’s] Macbeth — have conflicts going on that are perhaps the more satisfying elements of being an actor.

You’re seemingly in the prime of your career now, but I wonder if you’ve given any thought to that dreaded word — retirement?

I will stop if my voice breaks down. I wouldn’t want to inflict that on anyone. That would also mean I’m denying the audience of hearing someone sing better than me. I’m encouraged by the fact that people keep employing me.