One way or another, Meklit Hadero turns songs into communities and communities into songs.

Ever since arriving in San Francisco in the mid-aughts after graduating from Yale, the Ethiopian-born vocalist, multi-instrumentalist, educator, and composer has joined and founded multiple musical collectives and ensembles. In some cases, these projects have taken on a life of their own, turning into resonant, creative communions.

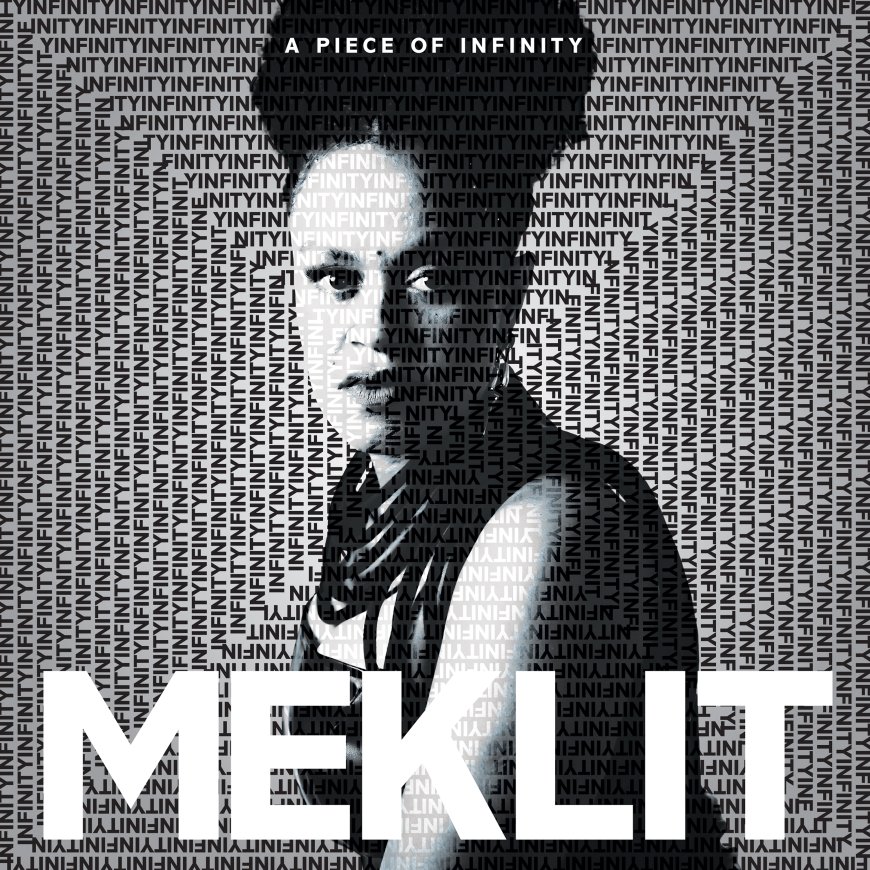

Released last September on Smithsonian Folkways, Meklit’s latest album, A Piece of Infinity, delves into traditional Ethiopian music. While her sources are folkloric, the songs are refracted through her long-running band steeped in jazz, R&B, and Ethio-jazz — a distinctive improvisational tradition that flowered in Addis Ababa in the late 1960s.

She celebrates the album’s release Saturday, Jan. 24 at the Freight in Berkeley, with saxophonist Howard Wiley, bassist Sam Bevan, drummer Colin Douglas, Marco Peris Coppola on Balkan percussion (tupan and davul), and Addis Ababa-reared keyboardist Kibrom Birhane. Rising Oakland singer-songwriter August Lee Stevens is slated to play an opening set.

“I’ve been watching August from afar, appreciating her genuine-ness,” Meklit told SF Classical Voice. “When she sings and plays, she’s truly communicating from a deep place. I love that. She’s Howard Wiley’s former student, and he’s been whispering in my ear about her.”

In many ways, A Piece of Infinity diverges sharply from Meklit’s last project, Ethio Blue (2024) — a pandemic-balm program of original songs created in collaboration with prolific Los Angeles producer Dan Wilson, though featuring the same core band as Infinity. She includes three originals on the new album, but Meklit gleaned the bulk of the material by researching the archipelago of peoples that make up Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most populous country with some 130 million citizens.

“The wonderful thing about Folkways is that they are all about music that has ancestral resonance,” Meklit said. She first connected with the label via her Kronos Quartet collaboration, “The President Sang Amazing Grace” — a track on Kronos’s 2020 Smithsonian Folkways album celebrating Pete Seeger, Long Time Passing.

With its legacy of documenting American roots music, she said the label offered her “an invitation to be part of the American folk canon, to be in relationship to it.”

“The album is really about Ethio-jazz and Ethiopian folk songs, and jazz in its origins being a folk music of Black America,” Meklit continued. “That’s a connection I make all the time.”

Recorded at Women’s Audio Mission, the San Francisco studio that has trained a generation of women sound engineers and techies, A Piece of Infinity was originally conceived via a grant from the Creative Work Fund. Further support from the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative cemented the project’s female-centric orientation.

“Every engineer who put hands on the album is a woman,” she said.

Guest appearances by jazz harp star Brandee Younger and flutist Camille Thurman, the first woman to hold down a chair in the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, weaves another layer of female creativity into the mix.

“That was part of the Smithsonian grant, making that connection to Black women jazz instrumentalists as it relates to jazz as a Black art form,” Meklit said. “They’re not only incredible musicians, they’re beautiful people, and collaborating was so natural and easy. It was wonderful to say, just be you, and we recorded them using whole takes so what you hear is what happened in the studio.”

In addition to her guitar work, Meklit defines the band’s harmonic palette on krar, a traditional Ethiopian six-string lyre. She’s gained real proficiency on krar in recent years but often defers to Kibom Birhane for passages on the pentatonic instrument. Based in Los Angeles, Birhane has been an essential part of her music since 2016, when he worked on her hard-grooving Six Degrees Records album, When the People Move, the Music Moves Too.

“He’s all over that record, and then we reconnected in recording Ethio Blue down in L.A.,” she said. “He grew so much as a musician between 2016 and 2019. Now he really plays krar in an ingenious way. He also plays bagana, an Amharic religious instrument that’s like a giant krar with 10 strings and a buzzy sound.”

Part of what makes A Piece of Infinity such a powerful record is that Meklit focuses her well-honed storytelling prowess on her own musical journey. In the past few years, she’s spent much of her time drawing out other artists via the multimedia empire Movement, a podcast, radio show, and concert series focusing on musical stories emerging from global migration. You might have also heard segments featuring Meklit on the public radio show The World.

“She’s always been very community oriented, tapping into something larger,” said bassist Sam Bevan, one of her most enduring musical collaborators. “She’s like gravity, and her energy pulls people toward her.”

The most recent project Meklit collaborated on was the Movement Immigrant Orchestra, which debuted in the summer of 2024 as part of the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival. The collective ensemble spun off of the live Movement productions, a series of city-specific events. But instead of taking the show on the road, she and her life partner, Italian-born percussionist Marco Peris Coppola, decided to start informal gatherings of artists with immigration stories to push back against pandemic-induced isolation.

The collective came to include a dazzling cross section of Bay Area artists, including Mexican singer/songwriter Diana Gameros, Malian string virtuoso Mamdou Sidibé, Spanish guitarist Javi Jimenez, Cuban trombonist Obrayan Calderon, Taiwanese cellist Roziht Edwards, and Haitian singer Lalin St. Juste.

But Meklit traces the origins of A Piece of Infinity back to an earlier collective, the Nile Project, which she founded in 2011 with Egyptian musicologist Mina Girgis. The musical and environmentally-minded transnational initiative brought together musicians from nearly a dozen Nile-traversed East African nations to share music, culture, and strategies for water conservation.

Meklit traveled with them across the region, “hanging out with traditional musicians at least 10 hours a day over a five-month tour.”

“They took me under their wing,” she recalled. “I started learning to play krar and knew I wanted to make a record of Ethiopian traditional music.”

In pulling the material together, she worked closely with Bevan, who co-produced A Piece of Infinity. While he moved back to the East Bay last year after a decade on the New York jazz scene, he never gave up his spot in Meklit’s band. A player who has thrived in a global array of musical settings, he brought deep respect and flexibility to the project.

“This is music that’s not part of the American landscape,” Bevan said. “It has really unique scales. With West African music you often have the blues as a reference. Ethiopian music is really different, a language that most people aren’t familiar with, so it’s tricky, and Meklit is making it accessible while putting her own stamp on it.”