Jim Kweskin has never been one to toot his own jug.

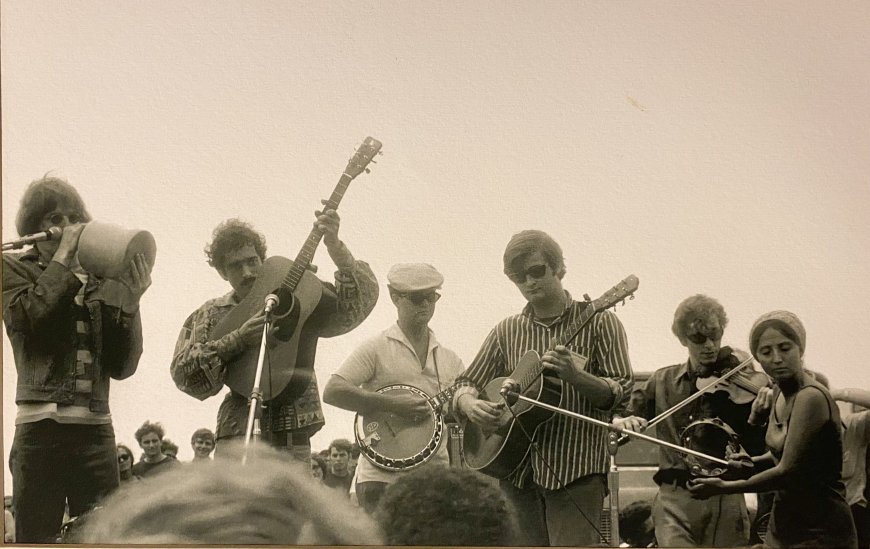

The singer and guitarist knows that his influence has been hailed by musicians and critics who cite the Jim Kweskin Jug Band’s emergence on the early 1960s Greenwich Village folk scene as a key cultural inflection point. Fresh Air rock historian Ed Ward, for one, has argued that the JKJB rivals the Beatles, the Byrds, and the Rolling Stones as a seminal force.

It’s true that Kweskin’s early albums for Vanguard Records directly inspired artists such as John Sebastian and The Lovin’ Spoonful, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Dan Hicks and His Hot Licks, and the Grateful Dead (who grew out of Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions). But on a recent phone call from his home in Boston, Kweskin sounded entirely unimpressed by the citations.

“We just started earlier,” he said. “All the bands that came after us, like John Sebastian, they listened to our records in high school. That’s natural. They all fell in love with the kind of music we played. I was influenced by the bands before me.”

Kweskin still has a passion for sharing songs, and he returns to California for a series of performances in the coming weeks, starting Saturday, Feb. 7 at McCabe’s in Santa Monica, where he’ll be accompanied by fiddler Benny Brydern and bassist Matthew Berlin; at Fifth Street Farms in Berkeley on Friday, Feb. 13, with bassist Matthew Berlin, Suzy Thompson on fiddle and vocals, and Meredith Axelrod on vocals and various instruments, including jug. Berlin and Thompson also join him at the Mercury Theater in Petaluma on Saturday, Feb. 14, and the Grange in Napa on Sunday, Feb. 15.

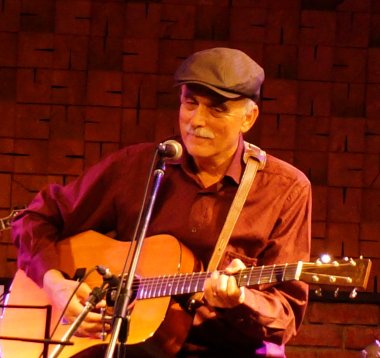

At 85, Kweskin has lost none of his musical prowess. His voice is supple and strong. His self-styled guitar work, fashioned out of close listening to ragtime, early blues, and old-time music practitioners, sounds as complete as ever. Part of what distinguishes him, for many of the musicians who were similarly besotted with the regional sounds of 1920s and ’30s vernacular American music, is that he never moved on to the next big thing, be it folk rock, psychedelia, or confessional songwriting.

He kept searching for obscure songs that deserved a new audience, while many of the JKJB musicians went on to major careers. Guitarist and vocalist Geoff Muldaur blazed a brilliant trail through the blues swamplands, while vocalist Maria Muldaur belted the blues with her then-husband, went on to “Midnight at the Oasis” pop stardom, and then back to the blues (the longtime Marin resident performs her Music For Lovers show with her Jazzabelle Quintet Friday, Feb. 13, at Firehouse Arts Center in Pleasanton and Saturday, Feb. 14 at Sweetwater Music Hall in Mill Valley). Bill Keith went on to a banjo career that earned him induction into the International Bluegrass Hall of Fame banjo career, and fiddler Richard Greene had already established himself as a bluegrass innovator when he joined the fold.

“I was never influenced by any of the bands that came after me,” Kweskin said. “I was listening to my contemporaries who were doing the same stuff, like ‘Spider’ John Koerner and Peter Stampfel and the Holy Modal Rounders. We’d hang out and I’d play a song for them that I’d found and they’d play a record they found, sharing our love of that music.”

The San Francisco-based Axelrod, who joins Kweskin for the Berkeley gig, is the most recent collaborator among the friends who’ll be playing with him. They first connected back in 2013 for a 50th JKJB reunion tour with Geoff and Maria Muldaur when Axelrod was recruited so the Jug Band would include a jug player.

“She came up on stage, played three or four songs and that’s all I knew about her,” Kweskin recalled. “But little by little I discovered, oh, she’s a great singer, and a guitarist, and a multi-instrumentalist. I had to do some gigs and she played with me at McCabe’s, a concert that became the album Come On In. I sell more of those than any other album, digitally or CDs, on Bandcamp and CD Baby. They even outsell my own jug band.”

Suzy Thompson, who re-established and ran the Berkeley Old Time Music Convention for more than two decades, started playing with Kweskin in the mid-aughts as part of the Texas Sheiks project with Geoff Muldaur. But she had a life-changing encounter with him decades earlier. Growing up in the Boston area in the early 1970s, she gravitated to Club Passim. Traveling on a shoestring to the Bay Area to visit a friend at UC Berkeley, she arrived in town and immediately made her way to Freight & Salvage.

“The admission was like $3, and Jim Kweskin was performing solo,” she recalled. “And it just blew my mind. I realized that a lot of the pop music I loved had its roots in jug band music. I was a huge Lovin’ Spoonful fan. I loved the stuff by the Kinks and the Grateful Dead too that was jug and skiffle band inspired. Kweskin was right in the middle of that.”

In many ways Kweskin and his song-sleuthing comrades were navigating the yawning, rapidly increasing divide between post-World War II urban and suburban America and its rural past. At the moment that television powered the homogenization of popular culture they were drawn to the unvarnished, idiosyncratic sounds of what Greil Marcus famously dubbed “the old, weird America.” So, how did Kweskin find these songs?

“I just got on Google,” he cracked. “Actually, there were many ways of finding these old songs, and a lot of them took work. I’d travel around to meet people with fabulous collections of old 78s. If they played me something I really liked, I had a little reel-to-reel machine and I’d record it — good enough to learn the song.”

Some of the music was starting to be reissued on vinyl. Tracks by early country star Jimmie Rodgers had resurfaced, and Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music rewired the brains of countless aspiring young musicians. And of course, in 1963, many of the artists who started recording before the war were still alive.

“I got to meet a lot of them, Jesse Fuller, Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James, Rev. Gary Davis,” Kweskin said. “All those guys recording in the late ’20s and early ’30s, that was only 10 or 12 years before I was born.”

Some of his folk scene contemporaries sought to preserve these old-time sounds, but Kweskin was never motivated by that kind of mission. He saw the acoustic idioms as a vehicle for self-expression.

“You make them your own,” he said. “Just because you’re taking a song somebody else did, you don’t copy it. We’re different people. I don’t cover songs. I uncover songs.”

More than 60 years later, Kweskin is still digging up treasure.