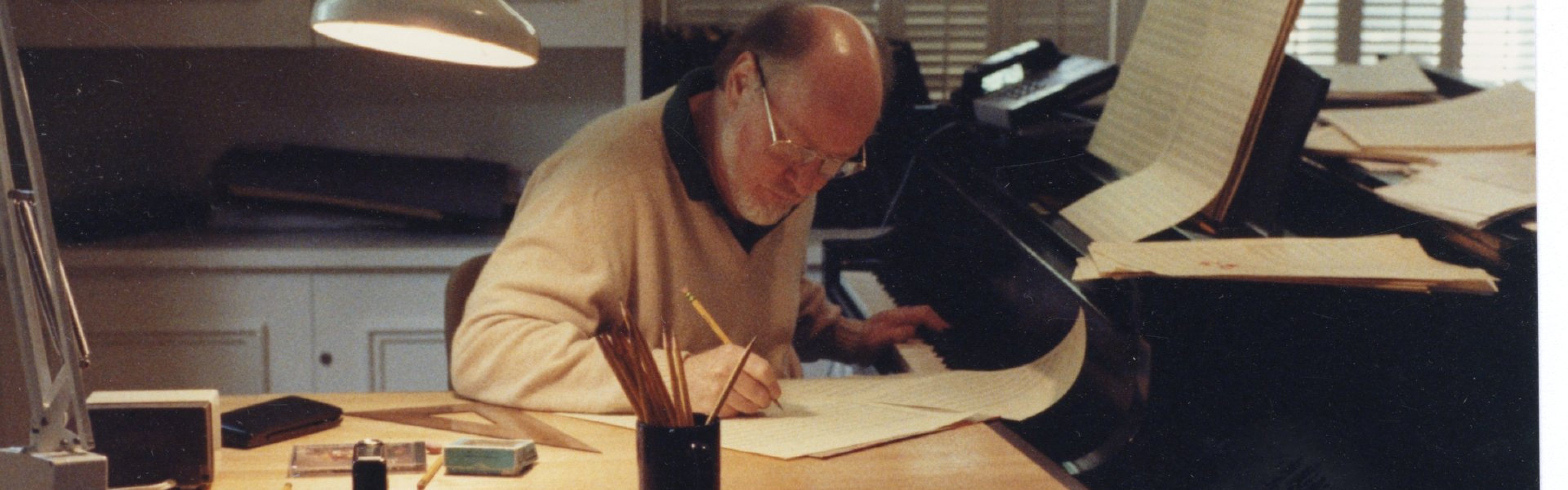

Film composer extraordinaire John Williams has led a charmed life. Tim Greiving's affectionate, eloquently written, and scrupulously documented biography John Williams: A Composer’s Life makes that abundantly clear. It has also been a uniquely American life.

Born into a New England musical family that encouraged his gifts and blessed with a "likable" and wholesome temperament, Williams grew up in an America of endless possibilities. Richly talented as a composer, he took advantage of every opportunity and enjoyed the role of a "third party" providing the "under-dialogue" that gives movies emotional depth and a "divine spark."

Nominated for 54 Academy Awards, more than any other living person, Williams has established himself as the most prominent and influential American composer for film of the last half-century. Greiving credits Williams’s success to his ability to convey the themes of "violence and elegy."

Optimistic, straightforward, and accessible, his film scores "gravitated toward the romantic and redemptive," Greiving writes. His brand of "highbrow populism" also jived with the confident and extroverted American mood of the second half of the 20th century. The sky was the limit — or not, as Williams showed in his enchanting celestial music for Steven Spielberg's classic movies of the world beyond, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Spielberg, Williams' soulmate and collaborator on 29 films in 50 years, has said that "John Williams is E.T." Greiving agrees, poetically:

"Where else did this man with his strange gifts come from if not the stars?” Greiving writes. “This wise, gentle being who reveals almost nothing about himself, but makes planets spin and touches peoples' hearts just by waving his hands. This profound channeler and director of emotions, who through some mystery can make us feel fear, or cause us to weep."

Greiving's book is not an authorized biography, but it comes close. Besides reading almost every word ever published about Williams and studying the music of the more than 100 feature films he scored plus his numerous serious concert works, Greiving also interviewed Williams. They talked on many occasions over a period of "18 ecstatic months" at the composer's home. They became friends. Greiving calls him "John."

Their personal relationship adds depth and intimacy to a book crammed with hundreds of anecdotes about his work with famous movie directors but the author's obvious admiration creates a reverential tone that sometimes blurs the traditional distance between biographer and subject. Writing a biography of a living person is always tricky.

I also wondered why this handsomely produced volume doesn't include a catalog or index of Williams's films and other compositions. This would have been helped readers making their way through a dense text packed with information, often presented in very long paragraphs in rather small print.

Greiving, a Los Angeles-based arts journalist, divides the book into two sections: Hollywood and Tanglewood. Movie buffs — especially those living on the West Coast — are probably less aware of Williams' longtime relationship with Tanglewood, the bucolic summer home of the Boston Symphony. He has conducted the Boston Pops there for many seasons beginning in the 1980s. Williams has rightly called Tanglewood the "high place in American musical life, a sort of Vatican."

In the verdant Berkshire hills of western Massachusetts, Williams explored the more "serious" side of his musical personality as a (mostly) beloved conductor and composer of non-film music. Especially in his later years, Williams sought to establish himself in the classical world, with mixed results. Some critics, composers, and musicians have dismissed his work as "pastiche, forgery, imitation," a judgment that has clearly rankled. In this regard, he identified strongly with Leonard Bernstein, who also moved at times uneasily between “high-brow” and popular culture.

Like other luminaries of Hollywood film music, Williams believes that there is "no essential distinction to be drawn between composing for films and composing for other media," as Christopher Palmer wrote in his 1990 book The Composer in Hollywood.

Greiving treats Williams' personal life in considerable detail, but his subject has been famously guarded about his own emotions. The defining tragedy in Williams' life was the sudden death of his wife and lifelong companion Barbara Ruick in 1974, at age 41, from a burst blood clot in her brain. There was no funeral, and he refused for many years to talk about her death with anyone, including his own children.

So perhaps it makes sense that such a private person would find his "hiding place" in film scoring, behind brilliant visual images created by others.

John Williams: A Composer's Life, by Tim Greiving, Oxford University Press, 2025, 630 pp.