Just a week after Halloween, Hector Berlioz’s spooky Symphonie fantastique took center stage at the Pasadena Symphony’s season-opening concert. Outside on Nov. 8, it was an appropriately foggy evening for devilish music. Inside the Ambassador Auditorium, Music Director Brett Mitchell warmed up the hall with a weighty program that also featured sunny jazz-inspired compositions by Maurice Ravel and Jim Self.

Beginning his second season with the Pasadena Symphony, Mitchell enjoys communicating with his audience and provided extensive descriptions and background for each piece, which made for a lengthy but educational evening.

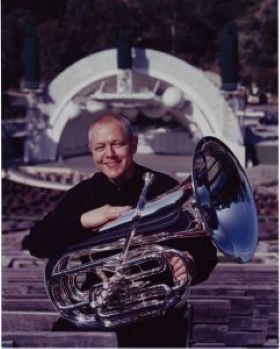

The program’s opener, held special personal significance for Mitchell and the orchestra. Besides his prolific life as a composer, Jim Self was Pasadena’s principal tuba for 50 years (1975–2025) and played in many other ensembles in the L.A. area. He also performed as a veteran studio musician on 1,500 soundtracks for film and television, becoming the “go-to” tubist for film composers. His most memorable gig was providing the “Voice of the Mothership” in John Williams’s score for Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Tour de Force: Episodes for Wind Ensemble was programmed as a 50th anniversary tribute to Self, assuming the composer would be there to take a bow. Sadly, however, Self died just days before the performance, at the age of 82. Mitchell called for a moment of silence in his memory.

The most popular of Self’s 90 published works, Tour de Force was inspired by the European tour he took with the Pacific Symphony in 2006. Scored for a large brass and woodwind ensemble with augmented percussion, it unfolds in nine loosely connected (and not programmatic) episodes. In a note, Self admitted that the piece was “certainly not classical, profound, or groundbreaking,” but “fun, mildly provocative, rhythmically interesting, jazzy, bluesy, and Latin at times.”

The Pasadena Symphony brass, woodwinds, and percussion made a strong case for this rousing and noisy curtain-raiser, which, not surprisingly, draws upon Self's long career in movie scoring for its energy, splashy sound effects, accessibility, and short attention-getting outbursts. The music may not be “great,” but the jazzy atmosphere and dynamic contrasts between larger and smaller groups of instruments made for an entertaining and ear-opening experience.

Tour de Force and the Ravel Piano Concerto in G Major that followed had something in common: the influence of George Gershwin. Episode Five of Tour de Force ends with a “Gershwin-like clarinet solo,” and the piece throughout uses the jazzy “stacked fourth” chords Gershwin was fond of.

Pianist Orion Weiss brought Ravel’s jazzy inflections to the surface of this performance in his delicate, perceptive, and refined interpretation. His account of the sublime second-movement Adagio followed a clear and lyrical line, with shimmering trills and hushed dynamics. Mitchell coaxed fine solo work from the woodwinds, prominent in the spare scoring. The racing downward scales of the final Presto had verve and propulsion, reminiscent of passages from Petrushka by Igor Stravinsky, Ravel’s contemporary in Paris.

Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique requires sustained energy and physical stamina from the conductor, orchestra — and perhaps the audience. Mitchell led with commitment and precision, showing that his connection with the orchestra has deepened since his inaugural season last year. One might have wished for a richer and more unified sound from the violins, led by concertmaster Aimée Kreston. The cello section played with confidence and a keen sense of the narrative line. Oboist Lara Wickes brought a pastoral calm to her solo in the third movement “Scene in the Country.”

The work tells a personal story of the composer’s own romantic obsession with the actress Harriet Smithson. Beginning in dreamy infatuation, it progresses, finally to diabolical ruin in a riotous sonic orgy, one of the great climaxes in the symphonic literature. If the level of intensity sometimes lagged here, Mitchell and the Pasadena Symphony still managed to capture the drama of Berlioz’s star-crossed journey.