Remounting a familiar production of Verdi’s Rigoletto may not be the most thrilling way for San Francisco Opera to open its fall season, but the choice proves rewarding in ways both musical and theatrical.

What makes the revival compelling — even after four return visits to it since a 1997 premiere (a 2020 run was canceled due to the COVID pandemic) — is the power of the work itself. Verdi’s masterly mid-career 1851 score and Francesco Maria Piave’s taut libretto, based on a Victor Hugo play, tell a ripe story of honor, betrayal, revenge and murder-for-hire. The composer lavishes his music on these themes with great dexterity and emotional allure, reminding us why Rigoletto has remained an indelible part of the canon for more than 170 years.

That dramatic tension is matched onstage during this latest return, which kicked off the 103rd Opera season on Friday, Sept. 5.

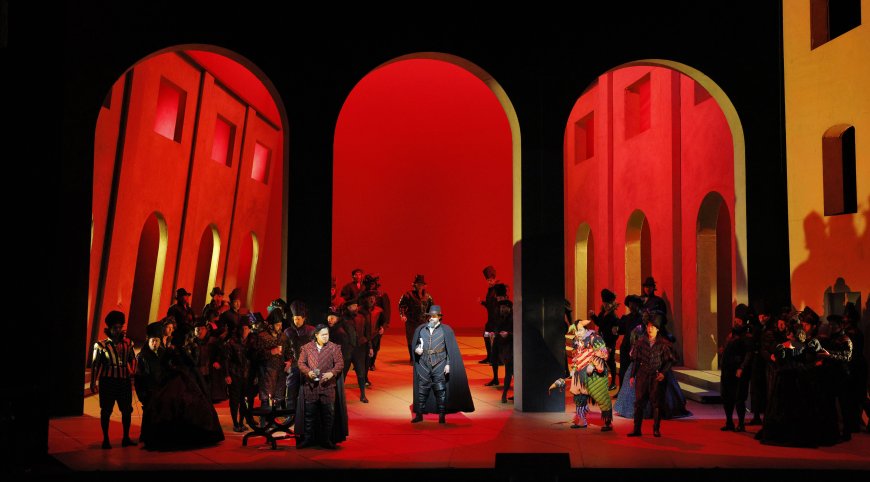

The narrative takes hold early on when a band of courtiers abducts the daughter of the title character, the sullen jester Rigoletto. The action plays out across the looming, forced-perspective arches, sinister alleyways and stark interiors of Michael Yeargan’s sets, inspired by the Surrealist paintings of Giorgio di Chirico. Mark McCullough’s lighting design, realized for this production by revival designer Justin A. Partier, sculpts the colonnades with insinuating glows and shadows, shoots a merciless spear of light through a doorway and bathes the entire stage in a ghostly, incriminating white.

The opera features solos and duets both romantic and wrenching, as well as absorbing scenes with larger ensembles. The well-deployed chorus powerfully captures the raw courtly and sexual politics of 16th century Italy. In one of many musically dramatic twists, Verdi gives his hit tune, the jaunty women-are-fickle canzone “La donna é mobile,” an eerie shiver when it’s reprised from offstage. Conducted by Music Director Eun Sun Kim, everything from delicate, wary pizzicati to a full-on thunderstorm rises from the orchestra pit.

In the cast that debuted on Friday, soprano Adela Zaharia made the keenest impression as Gilda — daughter of her tragically over-protective father, Rigoletto. Whether enchanted by the dissolute Duke of Mantua, sung with urgency by tenor Yongzhao Yu in his strong first appearance with the company, or in tender exchange with her fretting father, Zaharia brought a fluting tone and steely precision to the lyrical and technical demands of Gilda. In a role that can feel too sweet and cloying, Zaharia’s Gilda was imbued with strength and determination. Zaharia’s sense of purpose in the role, which played out to the opera’s shocking end, helped her Gilda sound and seem like a young woman of conviction and consequence.

Amartuvshin Enkhbat, who has performed the title role numerous times, brought a burly, barrel-chested baritone to his Rigoletto. But his static acting lacked the character’s pathos and poignant sense of isolation.

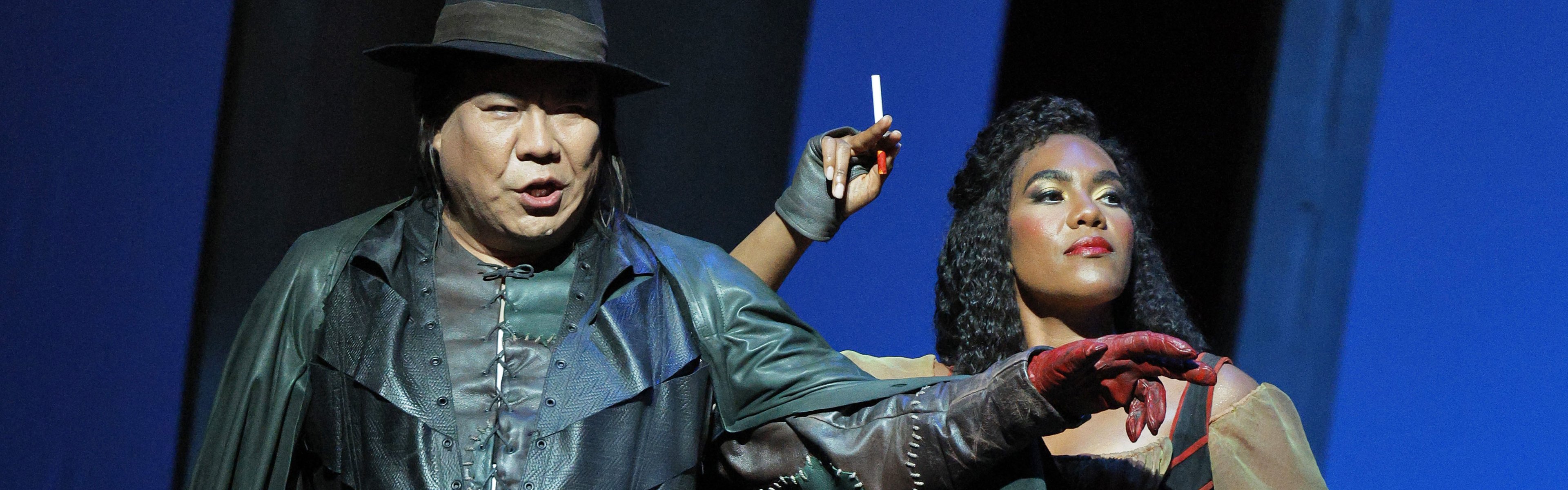

Among the smaller roles, company newcomer Peixin Chen used his skin-crawling bass and louche demeanor to craft a sinister Sparafucile, the story’s paid assassin. Mezzo-soprano J’nai Bridges, with her purringly seductive voice, was his volatile partner-in-crime. Aleksey Bogdanov delivered Monterone’s curse and bitter farewell in a thunderous baritone. Mezzo-soprano Stella Hannock sang Gilda’s animated companion with a sly sense of mischief.

The chorus sang with their customary assurance. After some early rhythmic mismatches between the orchestra and singers, Kim’s orchestra played with distinction.

Director Jose Maria Condemi’s staging was suitably and effectively pictorial. It’s no wonder the production keeps returning. At its best, this Rigoletto colors Verdi’s music drama in both the shadows and unforgiving blasts of light that memorably meld sight and sound.