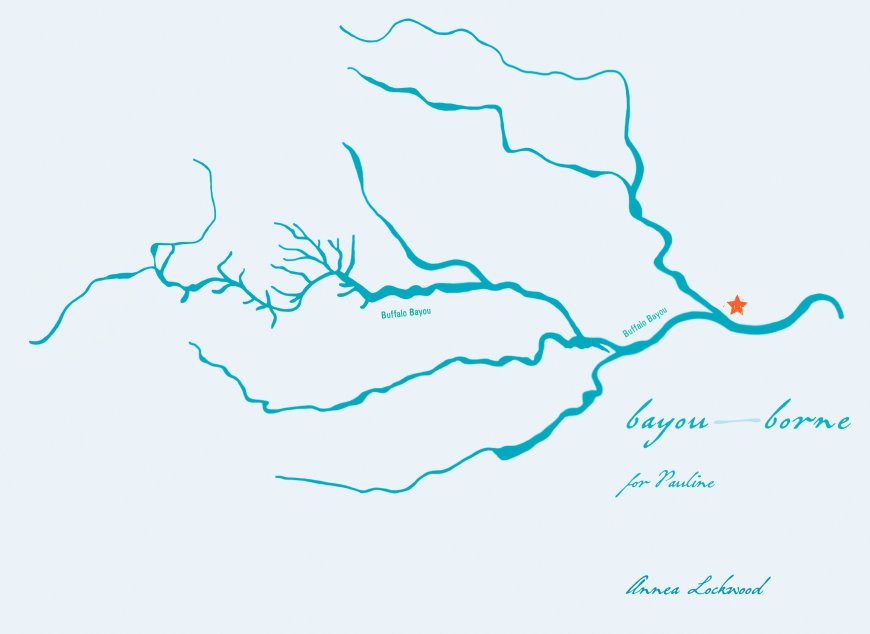

The score for Annea Lockwood’s 2016 composition bayou-borne, which was performed on the opening program of the 79th Ojai Music Festival, doesn’t include a single note. Rather, she provides a map depicting the massive confluence of rivers and streams that flow together to form Buffalo Bayou, the waterway that passes through Houston, Texas.

Lockwood’s map-score was the perfect metaphor for this year’s Ojai Festival — an international convergence of composers and musicians who came together to produce four memorable days of concerts under the leadership of virtuoso flutist Claire Chase, this year’s music director, and Ara Guzelimian, Ojai’s artistic and executive director.

As we face the threats posed by global warming and species extinction, Chase focused attention on women composers who hail from around the world: Lockwood (New Zealand), Susie Ibarra (U.S.), Tania León (Cuba), Liza Lim (Australia), and Anna Thorvaldsdottir (Iceland), among others. They are all creating music with perspectives that situate the listener in a complex web of connected issues and histories. Their compositions evolve across a cosmic, tectonic sense of time; incorporate Indigenous musical traditions and field recordings; and relay a message that the natural world is fragile and in danger.

And what better setting than the Ojai Valley for an outdoor festival stressing a spiritual connection to the natural world? Glaciers, rivers, raindrops, bird life, the “language” of forests, and the rumble of volcanos — all of these were directly evoked or sampled in the pieces Chase programmed Thursday through Sunday, June 5–8.

Libbey Bowl was the perfect venue to host this environmental theme, for every concert there is accompanied by croaking frogs, twittering crickets, hooting owls, and cooing doves, while sunlight dapples through the leaves and the moon slowly rises.

Opening night was magical, one of the most captivating concerts I have experienced at this festival. With hindsight, I can say this is because we were at the start of a journey through ideas as well as music.

Lockwood, 85, was making her first Ojai appearance in this concert. Bayou-borne was created to honor a close friend, composer Pauline Oliveros, on her 85th birthday. Sadly, Oliveros died shortly before reaching that milestone, yet in a sense, she was the originating spirit of Chase’s festival.

Oliveros championed what she termed “deep listening,” which asks audiences to open themselves to the spiritual depth of a musical experience. She called it a “practice” and explained, in words that echoed throughout this festival, “deep listening involves going below the surface of what is heard, expanding to the whole field of sound while finding focus. This is the way to connect with the acoustic environment, all that inhabits it, and all that there is.”

The almost totally improvised structure of bayou-borne provided an exquisite introduction to Lockwood’s free-flowing process of composition. The piece also introduced an ensemble of artists who would perform in various configurations throughout the festival: clarinetist Joshua Rubin, Chinese sheng player Wu Wei, trumpeter Dan Rosenboom, trombonist Mattie Barbier, M.A. Tiesenga on electronic hurdy-gurdy, and percussionists Ibarra, Steven Schick, Ross Karre, and Wesley Sumpter.

As described in the program book, “Lockwood translates map lines into parts, leaving it to the performers to make decisions about such factors as tempo or density of the musical texture according to where their lines thicken or curve.”

But a listener, without being told, might never have known that Thursday’s performance was improvisational, so fluid was its execution. These musicians, all of them long accustomed to this way of working, created a performance that was so cohesive that it seemed like they were elaborating a composed score rather than improvising off a map that was projected on a series of screens.

Closing out opening night was Marcos Balter’s Pan, which Chase premiered in 2018 as part of her ongoing commissioning project Density 2036. The 90-minute-long work, in nine sections, tells the story of the mythological demigod and satyr who grew so proud of his musical prowess that he challenged Apollo to a competition. Pan lost and was forced to pay for his hubris.

Balter’s score is a masterpiece of musical artistry and dramatic storytelling, and Chase’s performance showed off her virtuosity and endurance. Fully staged with projections and elaborate lighting, this presentation featured a chorus made up of Ojai locals and audience members ranging in age from 9 to over 80.

Entranced by the magic of his flute song, the ensemble worshiped Pan like a rock star, only to turn on him after his defeat. All the while, the natural world, Pan’s domain, contributed its sounds, and the choristers, with lights on their fingers, moved through Libbey Bowl like forest spirits led by Chase’s flute. It was an Ojai moment like no other.

Another festival highlight came mid-Sunday morning in Ibarra’s 2025 Pulitzer Prize-winning composition Sky Islands, whose title refers to the high-altitude rainforests of the island of Luzon in the Philippines. It’s an endangered ecosystem that sits above low-lying clouds and is populated by animals found nowhere else.

Ibarra creates a panoramic sense of this unique environment, beginning with the rhythmic pounding of large bamboo poles. Indigenous dance rhythms blend with evocations of the natural world, accentuated by the rustling of huge palm leaves and a vast array of percussion instruments, including a battery of tuned gongs. The work was performed with a sense of pure delight by Chase, dual percussionists Ibarra and Levy Lorenzo, pianist Alex Peh, and the JACK Quartet: violinists Christopher Otto and Austin Wulliman, violist John Pickford Richards, and cellist Jay Campbell.

Traditionally, Ojai features a series of “Morning Meditation” concerts that begin at 8 a.m. Saturday’s open-air offering took place deep in the woods of the 58-acre Ojai Meadows Preserve. With the land shrouded in mist, the performance commenced with Ibarra’s harmonic convergence of instrumental avians, Sunbird (2021). The piece was so effective it was almost impossible to tell which sounds came from the musicians and which came from actual birds.

The concert that followed at 10:30 a.m. in Libbey Bowl ended with a towering performance of Thorvaldsdottir’s Ubique (2023), a 45-minute work composed for Density 2036. Powerful and disturbing, the piece is as dark and brooding as the Icelandic landscapes it evokes. Chase, pianist Cory Smythe, and cellists Katinka Kleijn and Seth Parker Woods performed the work, its thematically mirroring movements separated by the deep, ominous rumbling of a recorded volcano, as if to warn, “Something wicked this way comes.”

And then there was Lockwood’s 2010 soundscape A Sound Map of the Housatonic River, presented Saturday and Sunday at the Move Sanctuary yoga studio. The audience lay on mats or sat against the wall surrounded by a four-channel array of speakers. What followed was a collage made from multiple years of field recordings of the Housatonic River, from its headwaters to its outflow delta at the Long Island Sound.

The experience, however, was anything but documentary, and Lockwood sees her work as a musical composition. She painstakingly edits and cross-fades her recordings, here producing a musical tour de force of constantly shifting rhythms, multilayered tonalities, and vibrant colorations. This music isn’t made by instruments but by the endless variations of water flowing, birds singing, cicadas buzzing at nightfall, and even a train passing, ending with the soft lapping of waves on the shore.

For audience members, it’s a journey that requires patience and a willingness, quite literally, to go with the flow. It’s one of the masterworks of the 21st century. And like the rest of this year’s festival, the experience invited listening on multiple levels, incorporating the sounds around us as an integral part of the composition. Somewhere, Oliveros’s spirit was smiling.