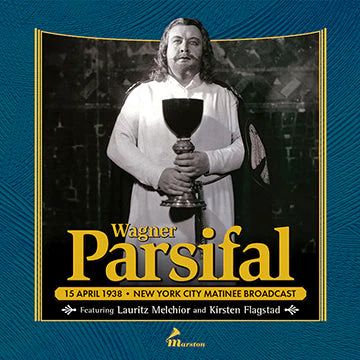

In the esoteric world of Wagner historical recordings, there are a few items that are considered to be the equivalent of the Holy Grail — long-sought, legendary artifacts that finally turn up after being hidden away for decades. Two examples are the Wilhelm Fürtwangler 1953 Rome Ring cycle and Hans Knappertsbusch’s Götterdämmerung from the 1951 Bayreuth Festival. The latest find is a 1938 New York Metropolitan Opera broadcast of Parsifal, documenting a stellar cluster of golden age Wagnerian singers and a real-time passing of the baton from an old-school veteran to a gifted newcomer on the road to fame.

Why is this a big deal for Wagnerians? It appears to be the only complete recording of two Scandinavian superstars of their time, soprano Kirsten Flagstad and tenor Lauritz Melchior, in their roles as Kundry and Parsifal respectively. On top of that, the great Wagnerian baritone Friedrich Schorr is on board as Amfortas, and the sturdy bass Emanuel List takes the marathon role of Gurnemanz. Another unusual thing about this recording is that the opera is uncut; this at a time when most Wagner operas — and several by others — were riddled with cuts in live performance. A Holy Grail indeed, especially since Parsifal’s storyline is built around the actual fabled sacrament.

According to co-producer and veteran restoration engineer Ward Marston —whose eponymous label issued a four-CD set of the discovered recording — earlier bootlegs of this broadcast were poor-sounding and incomplete. Marston has had a complete set of 16-inch aluminum lacquer-coated transcription discs in his possession since 2006 but found it impossible to create an acceptable transfer with the technology of the time. With more sensitive, advanced, noise-removing software now available, Marston was finally able to get results he thought were worth releasing.

The low-fi sound is still not very good, not even close to the standard of 1938-vintage 78s. There are few highs, almost no bass, constant surface noise, and some serious static that sounds like sandpaper grinding in the middle of Act I. I have not heard the previous attempts at issuing this performance and can’t imagine how bad those must sound.

Yet this is it — and from behind the flat sonic haze, Flagstad’s unmistakable timbre manages to peek through, as does her multifaceted portrayal of Kundry, going from the whimpering near-animalistic persona in Act I to a convincingly sultry seductress in Act II and humbled penitent in Act III. Melchior’s unique, somewhat-baritonal Heldentenor doesn’t quite come into its own until the point in Act II when he receives the kiss from Kundry, after which he is at his ringing best. Schorr is impressive throughout, List is a steady, authority-wielding Gurnemanz, and baritone Arnold Gabor seems to relish the role of the evil Klingsor.

Artur Bodanzky, the Met’s resident Wagner specialist at the time, conducts Acts I and III, but — in a most unusual move — he hands the baton over to 26-year-old Erich Leinsdorf for Act II. Milton Cross, the imperturbable Met radio announcer who kept going into the mid-1970s, explains on the broadcast that Bodanzky arose from his sick bed to conduct and gave Act II to Leinsdorf so he could rest up after the long, taxing opening act. This sets up a fascinating contrast between a fading maestro (he passed away the following year) and a young Austrian immigrant on the move, who would soon inherit Bodanzky’s role as the Met’s head of German repertoire.

Bodanzky’s Act I Prelude is very slow, surprisingly so, and quietly meditative, yet once he gets into the first scene, he ratchets up the tempos, allowing occasional old-fashioned portamentos in the strings. Leinsdorf rushes into the Act II Prelude like a house afire, offering a more objective 20th-century approach, eschewing string portamentos except in one instance, while producing some soulful playing after Kundry’s entrance.

The portamentos come flooding back when Bodanzky returns to the pit for the Act III Prelude, and he finds new strength and eloquence all the way through to the final pages, which make their magical impact. The Met orchestra is not top-notch, not like it would be decades later under James Levine. But then again, whatever instrumental luster there may have been in the opera house that afternoon is lost on these resurrected lacquers.

The compact package includes a long, well-written, invaluable essay on the early history of Parsifal at the Met by San Francisco Opera’s Jeffery S. McMillan, and another by Marston about how this recording came to be. At the end of his essay, Marston expresses the hope that this set will take an important place in the history of Parsifal recordings. For all its sonic flaws, it will – and should.