Lesbian love, infidelity, incest, fratricide, and a quick dose of male hysteria, all intertwined with the spirits Cassandra and Antigone: how’s that for the plot of an incomplete, early-20th century French opera that finally received its first fully staged production in 2024?

Nadia Boulanger (1887–1976), the great pedagogue and composer, wrote La ville morte (The Dead City) between 1909 and 1913 with her mentor and lover, organist-pianist Raoul Pugno (1852–1914). A planned premiere of La ville morte at the Opéra-Comique in 1914 was aborted due to the outbreak of World War I and, perhaps, Pugno’s death on January 3. Although Boulanger seems to have worked on the opera as late as 1923, whatever orchestration she completed was lost during the war. Only the piano-vocal score survived.

Enter Neal Goren, founder and artistic director of New York’s Catapult Opera. After consulting with a number of Boulanger’s last living pupils, including San Francisco Conservatory professor/composer David Conte, Goren learned that Boulanger would have “preferred distilled, clear presentation, and she would have chosen a chamber orchestration for both artistic and practical reasons.” Goren then co-commissioned Joseph Stillwell and Stephan Cwik to orchestrate the work, with artistic oversight by Conte.

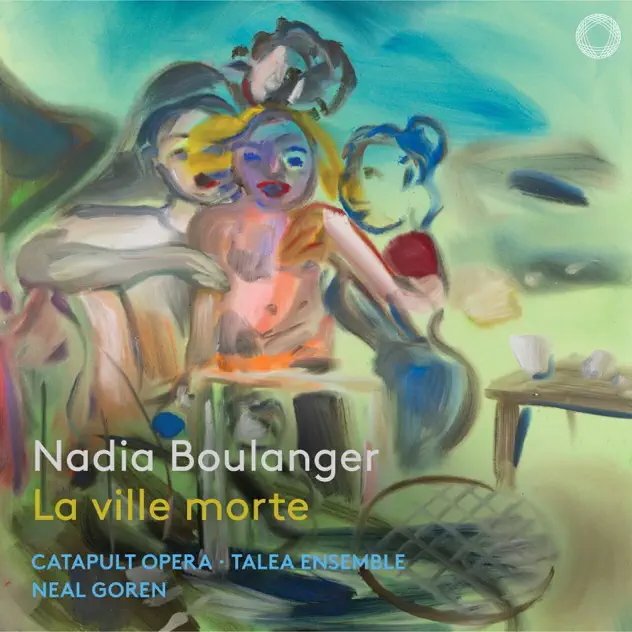

Greek National Opera presented La ville morte in January 2024, then Catapult Opera’s three performances followed in April 2024 at NYU. A live recording was captured of the co-production, featuring soprano Melissa Harvey (Hébé), mezzo Laurie Rubin (Anne), tenor Joshua Dennis (Léonard), and baritone Jorell Williams (Alexandre), with the Talea Ensemble conducted by Goren.

A simple plot summary goes like this: Hébé and Léonard are brother and sister. Léonard and Alexandre are best friends. Alexandre is married to Anne. Anne and Hébé are in love. To complicate matters, Léonard is in love with his sister, as is Alexandre. And as much as Hébé’s verbal exchange with Alexandre suggests that the two resist temptation, a musical interlude proclaims something very, very different. What the libretto may not say, Boulanger and Pugno’s score makes explicit.

The opera’s libretto, which owes more than a few of its elements to Maurice Maeterlinck’s 1892 play Pelléas et Mélisande and some of its atmosphere to Debussy’s opera of the same name, was the work of Italian poet and novelist Gabriele D’Annunzio. D’Annunzio, who also penned the text for Debussy’s Le martyre de Saint-Sébastien (1911), based the libretto for La ville morte on his own 1898 five-act play of the same name, albeit in Italian.

Boulanger’s score for La ville morte reflects the French and German musical language of her period. Despite anything anyone might wish to say about French refinement, the music’s frequent prolonged outbursts of forbidden passion are as hothouse as it gets. It helps to know that Nadia’s guardian, Ernest Boulanger (winner of the Prix de Rome), was not her biological father and that her lover, Pugno, died in her arms.

The music is gorgeous, and sometimes offers surprises. What are we to make, for example, of the serene prélude to the fourth, act which immediately cedes to the discovery of Hébé’s body? Does Léonard really go nuts or is he incapable of accepting his culpability? As for the final surprise, what does it mean?

Ultimately, one thing is clear. The opera’s glorious music is extremely seductive. I urge you to partake of its glories. Both male leads sound a mite pinched on top, but they and their female counterparts sing with total conviction.

The recording is available from Pentatone on streaming platforms or as a high-resolution digital download, with a CD release scheduled for September 2026. Having auditioned the download, my hat goes off to producers and engineers Adam Abeshouse and Doron Schachter for their achievement. Equal congratulations to Goren, Conte, Stillwell, and Cwik. I couldn’t stop listening.