Mozart is timeless. It increasingly appears the play, Amadeus, is as well.

Peter Shaffer’s masterpiece of speculative historical fiction, in which composer Antonio Salieri rivals Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, has been around for nearly a half-century. But the popularity of the 1979 work has clearly not waned.

Pasadena Playhouse’s new production, directed by Tony Award-winner Darko Tresnjak, opens Feb. 11 and has already been extended to March 15.

One can only speculate why the melodrama — in the best sense of the word — remains an audience favorite. But the play’s focus on jealousy, self-loathing, the loss of religious faith, and the slippery nature of success are no doubt highly relevant to today’s internet-addicted culture.

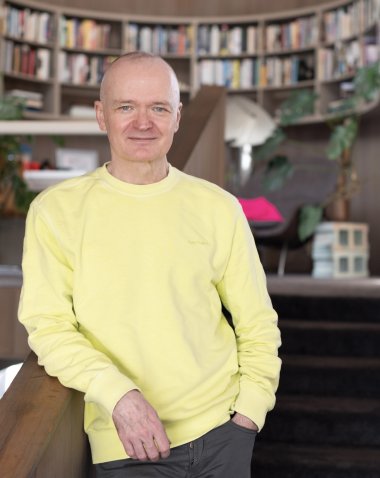

“We as a society seem more preoccupied with fame these days,” said Jefferson Mays, the veteran actor who will play Salieri. “Everybody is on social media. They ascertain their self-worth by how many ‘likes’ they get. It’s almost toxic.”

During his lifetime, Salieri got more than his share of “likes,” rising to the top of his profession and riding a wave of acclaim and success. But like so many of the habitually online, he discovered shallow popularity left him feeling empty. When Salieri realized his young colleague, Mozart, was a genius whose music would long outlive his own, he was plagued by resentment which, at least in Shaffer’s play, curdled into a desire to murder.

“I came across this wonderful quote from Schopenhauer, which I will proceed to butcher: ‘Talent is able to hit a target nobody else can hit. Genius is able to hit a target nobody else can see.’ That really sums it up for me,” Mays said. “Salieri is painfully conscious of the fact that he is in the presence of true genius.

“He gets up every morning trying to destroy what he loves most in the world,” Mays continuged. "It’s a warped love story.”

Amadeus was a huge success as soon as it premiered in London. However, Shaffer kept tinkering with it for decades. Tresjnek and his cast are using the playwright’s sixth and final version, while occasionally looking at earlier drafts to get a sense of his original intentions.

The fact Shaffer couldn’t stop revising the play “tells you so much about his mind,” Tresjnek said. “After it won the Olivier and Tony awards, and the movie won the Oscar, he still won’t let go of it. Now that we’ve staged that last scene between Mozart and Salieri, it’s as good a piece of writing as I’ve ever directed.”

To Mays, Shaffer’s constant revising suggests the playwright might have felt a kinship with Salieri. Critics routinely wrote that, while his work was effective, Shaffer wasn’t at the level of Harold Pinter or Tom Stoppard.

“He was always called a ‘workmanlike playwright,’ which he always resented, asking ‘What’s the alternative?’” Mays said. “I think that’s what drew him to the subject.”

The opportunity to reunite with Mays drew Tresjnek to the Pasadena Playhouse production. Their previous collaborations include the Broadway musical A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder, which won Tresjnek a Tony Award in 2013. “If Jefferson is interested in doing something, I’m interested,” he said.

Given this is the first time either of them have worked on — or even seen — the play, their fresh eyes have led to some interesting discoveries. Tresjnek, like many of his predecessors, puzzled over the immature, scatological Mozart of the play — a portrait that reflects Shaffer’s extensive research. The director concluded Mozart’s bad behavior reflects a sort of delayed adolescence, “the result of his overbearing father.”

“Overbearing is a kind description! His father had a financial advantage to keep the wunderkind a wunderkind. There was psychological damage as a result. When I came across that in my research, I thought, ‘Bingo. That’s how you reconcile the two sides of Mozart.’”

That notion has informed Sam Clemmett’s portrayal of Mozart (who, as part of his preparation, received a conducting lesson from James Conlon). “He’s less the buffoon than in the film,” said Mays. “With Sam, you believe this person was capable of producing this music.”

Salieri’s mental state also plays a huge role in Tresjnek’s conception of the play. “Salieri never leaves the stage, so the idea of setting the play in his deranged mind, his violent imagination, seems right,” he said. “It’s also a gift for designers, since it’s very liberating. The set is inspired by the Schönbrunn Palace, along with Ingmar Bergman’s film Cries and Whispers, which takes place in red rooms with black and white costumes.”

Besides his stage work, Tresjnek has directed many opera productions. His connections to LA Opera came in handy for this show, as the company has supplied three singers to perform live music in the production. In addition, young performers from the Pasadena Conservatory of Music will give 10-minute micro-concerts of Mozart’s music in the Playhouse’s restaurant space 30 minutes before each show.

Both Mays and Tresjnek have long been in love with Mozart’s music. “I grew up listening to WQXR in New York; I remember it being on in the kitchen,” Mays recalled. “I loved Mozart from a very early age. I particularly love the String Quartet No. 19 in D Major, the ‘Dissonant.’ The beginning is extraordinarily modern to my ears — it’s so unsettling. I begged to put it into the play.”

Tresnjek grew up in Washington, D.C., and remembers seeing Mozart productions at the Washington National Opera at a young age, including The Magic Flute designed by Maurice Sendak. During his long career as a director of both plays and operas, Tresnjek has staged that great work, as well as The Marriage of Figaro and Cosi fan Tutti.

“I’ve never directed Abduction from the Seraglio, but I’d love to, in case anyone who runs an opera company is reading this,” he said. “In the play, Salieri criticizes the aria ‘Martern aller Arten’ from Abduction. It happens to be the piece that I shower to — it’s the perfect length for a shower. I listen to Diana Damrau. It’s all sectioned off, so I know when it’s time for shampoo and conditioner.”

Well, why not? As Salieri knew better than anyone, Mozart was head and shoulders above the rest.