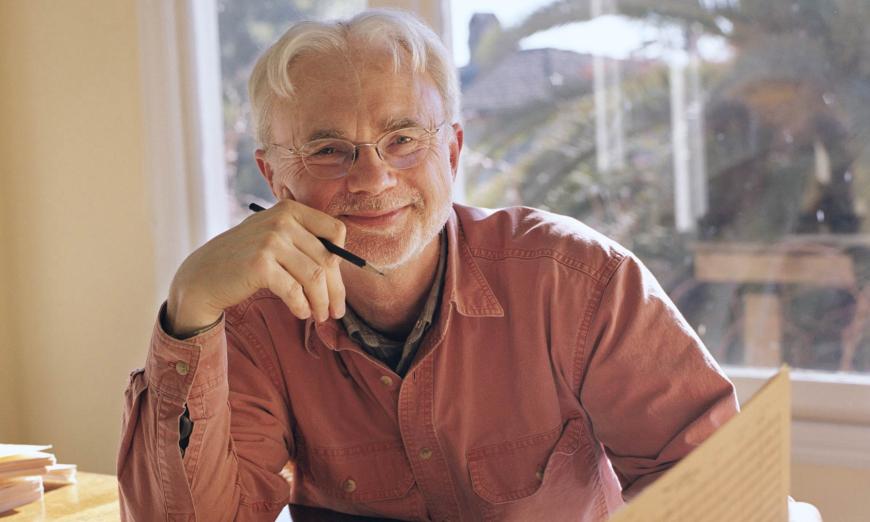

The Los Angeles Philharmonic is off to a roaring start in 2026. Hot on the heels of Esa-Pekka Salonen’s triumphant two-week return to Disney Hall, the orchestra offered another unusual and rich assortment of music by three generations of American composers, conducted by composer and LA Philharmonic Creative Chair John Adams.

The LA Phil premiere of Adams’s remarkable piano concerto After the Fall (2024) took the spotlight in a riveting performance by pianist Víkingur Ólafsson, for whom it was written. At the end of this absorbing and thoughtful evening, I felt pride and hope for America’s musical and cultural heritage in the 250th anniversary year of our country’s founding.

Co-commissioned by the San Francisco Symphony (with multiple partners, including the LA Phil) and first performed there last season, After the Fall takes its title from the idea that after the musical avant-garde has fallen from favor there’s always J.S. Bach for inspiration. Ólafsson’s performances of music by Adams, and of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, deeply influenced the composition, which concludes with an infectious and extended “infiltration” of the C-Minor Prelude from Book I of Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier.

In its transparent, lyrical style, After the Fall differs from much of Adams’s denser and more dissonant recent music and seems to reach back to his accessible early works like Harmonielehre and Shaker Loops. Using an enlarged percussion section, the concerto treats the piano more as an integrated member of the dreamy and often delicate sonic ensemble than as a vehicle for solo statements. But the piano is rarely silent throughout, and becomes more prominent in the finale, with virtuosic fleeting passages in imitation of Bach.

The string sections play a secondary role, providing a solid base of support (often in unison) for the more active and frequently changing patterns in the winds and brass. The three “movements” flow without pause, similar to the form favored in the symphonies of Jean Sibelius, a composer Adams admires.

At the keyboard, Ólafsson found the perfect balance between delicacy and aggression, merging seamlessly with the orchestra and forging the link between present and past that is the essence of After the Fall. Following a tumultuous ovation, Ólafsson offered a heartfelt spoken tribute to Adams and their collaboration. “I’ve been listening to his music since I was 12 or 13. What I admire is that he stares into the future, asks if there is still space to create, and answers in the affirmative. John likes to work and likes us to work.” He then gave his encore, Bach’s Prelude in E Minor (from WTC, Book 1) in an arrangement by Alexander Siloti.

As in the San Francisco premiere, Adams preceded the concerto with Charles Ives’s philosophical musical treatise The Unanswered Question. Inspired by the writings of transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, three instrumental timbres — a trumpet, four flutes, and strings — engage in a five-minute conversation about nothing less than existence and eternity. Trumpeter Thomas Hooten, playing from the rear of the top balcony, made the hall ring with his glowing tone; the flutes, in the choir seats, answered across the soaring space. Adams conducted with subtle command, joining the players in what sounded like an invocation and plea for peace.

Two standards occupied the second half. Born only two years apart, Aaron Copland and Roy Harris both spent time studying in Paris, but later strove to write music that sounded uniquely “American” — with long, soaring lines, wide open spaces, and a homespun folksiness. While Harris never achieved Copland’s popular success, his underappreciated Symphony No.3 (1938) established him as an important vernacular voice. Hearing this somber, epic work under Adams’s idiomatic direction came as a revelation.

Disney Hall vibrated when the stellar cello section intoned the broad opening theme, establishing the pensive mood, so evocative of Depression-era America. The symphony’s five main sections, which function as uninterrupted “movements,” wind their way through a pastoral theme in the flute to a syncopated hoedown tossed around the orchestra with frontier vigor. A relentlessly beating timpani reestablishes the opening tragic atmosphere.

Copland’s Appalachian Spring may be overexposed on the radio and in popular culture, but a nuanced and intricately detailed performance like this one still inspires awe. The suite for large orchestra retains the chamber-like proportions of the original dance score, which was composed for the Martha Graham Dance Company.

Clarinetist Boris Allakhverdyan set the stage for this “pioneer celebration” with a sweetly soulful statement of the simple opening theme, rising and falling by hollow thirds. Oboist Ryan Roberts and flutist Denis Bouriakov offered subtle, organically phrased playing as well.

Adams’s comfortable, leisurely tempos and restrained volume levels conveyed the joy and apprehension of the scenario’s newly married couple. Quiet and strong, the performance penetrated to the heart of this American classic